Improving the Electoral Count Act isn’t enough to protect voting rights and stop election subversion.

While voting rights legislation is pretty much doomed due to Republican opposition and moderate Democrats’ decision to keep the filibuster intact, there’s still hope for a much narrower election reform: changes to the Electoral Count Act (ECA).

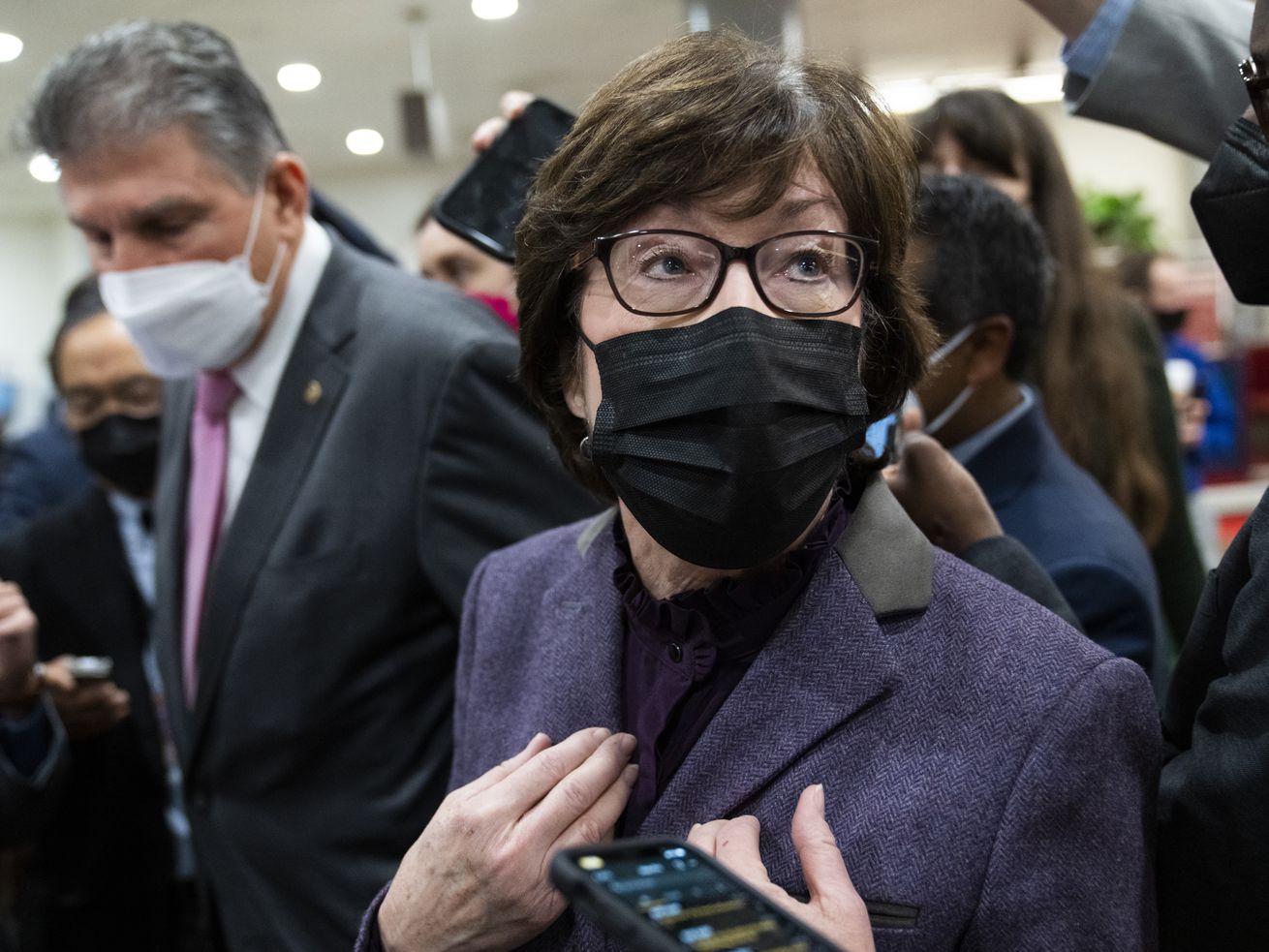

A bipartisan group of roughly 12 lawmakers, including Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME), Mitt Romney (R-UT), and Joe Manchin (D-WV), is now in talks about possible ECA updates, though it’s unclear if enough Republicans would ultimately sign on to reach the 60-vote threshold any bill needs to pass. Because the law governs how Congress counts presidential election results, reforms could address vulnerabilities that former President Donald Trump tried to exploit last January.

These updates, however, wouldn’t bring about the sweeping protections Democrats hoped to institute with the voting rights package that failed this week, and wouldn’t be enough to stop election subversion at the state level. The push to reform the ECA is also indicative of the legislative limits the party faces with the filibuster intact. Because they need GOP support for most bills, Democrats might be able to take some small steps toward their policy goals, but only the ones that Republicans allow.

“American democracy faces multiple threats — the possibility of interference with the electoral count is just one of them,” said Alex Tausanovitch, the director of campaign finance and election reform at the Center for American Progress. “Just reforming the Electoral Count Act would be like only locking your back door. There’s a broader set of precautions we should take, particularly when something as fundamental as the democratic process is at stake.”

Like Democrats’ push to pass new federal voting rights protections, updates to the ECA are a direct response to Trump’s attempts to overturn the 2020 election results, though they only address one aspect of these efforts.

As Congress was certifying election results last January, Trump urged Vice President Mike Pence to throw out certain results, something Pence ultimately declined to do. Modifications of the ECA could make it clear that a vice president is unable to discard election results, and thus unable to overturn an election. In addition, the updated ECA could make it tougher for lawmakers to challenge states’ results, thereby avoiding a situation where a group of lawmakers conspires to nullify valid election results as some Republicans attempted to do in 2021.

Although these reforms are critical and worth pursuing, election law experts say they’re no replacement for measures intended to increase voting access and combat attempts at partisan election interference in different states. Because reforms to the ECA would narrowly apply to Congress’s role in presidential elections, they wouldn’t confront state laws that restrict early voting access and vote-by-mail, and they wouldn’t counter state legislatures’ attempts to exert control over local election administration. Collins has said she hopes a bipartisan elections measure could also help strengthen protections for poll workers and election officials who’ve faced growing threats of violence. The limitations of these possible reforms, though, have not escaped notice from some Democratic lawmakers.

“I support reforming the Electoral Count Act,” said Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) in a floor speech on Wednesday. “That said, reforming the Electoral Count Act will do virtually nothing to address the sweeping voter suppression and election subversion efforts taking place in Georgia, and in states and localities nationwide.”

The Electoral Count Act, briefly explained

The Electoral Count Act, which was first passed in 1887, lays out how Congress counts each state’s electoral votes in a presidential election, and how lawmakers should respond if states send in competing sets of results.

As it works now, Congress receives the presidential election results from each state and has the job of counting and certifying, or finalizing, these results. To do so, Congress gathers the January after the presidential election for a joint session in order to go through each state’s results. As the results are read, lawmakers can contest them as long as one House member and one senator agree to register their objections.

If an objection is made, the House and Senate will then each debate the objection and vote on it: For the results to actually be contested, a majority of members in both bodies need to agree to it. Otherwise the objection is dispensed with and the results are counted as is.

This provision in the law was particularly relevant last year.

In January 2021, House Republicans raised objections about the results in six states, though only their objections toward the Arizona and Pennsylvania results had Senate support. Neither of those objections received a majority of support in either chamber.

In the past, lawmakers have raised objections regarding the Georgia results in Trump’s election in 2016 and the Ohio results in former President George W. Bush’s election in 2004. The objections to the 2020 presidential results, however, were unique in the number of states that were contested, and the number of Republicans who supported the effort. In the end, 147 Republicans maintained their objections to the outcome in Pennsylvania or Arizona.

During the certification process, the vice president also has what’s typically a ceremonial role that’s detailed in the ECA. Their job is to open each state’s electoral results, present them to Congress and preside over the joint session. Once the outcomes in each state are tallied, the vice president will also announce which candidate received a majority of the electoral votes to win the presidency.

In 2021, however, Trump urged Pence to consider overturning the results by rejecting the outcomes in several states. According to Peril, a book by Bob Woodward and Robert Costa, attorney John Eastman, a member of Trump’s legal team, laid out a plan for how Pence could discard the electoral outcomes in seven states and declare Trump the winner. Pence, however, concluded there was no legal basis for him to do so and refused to follow through on the plan. Changing the ECA would further guarantee that a vice president wouldn’t be able to take such actions.

As a Yahoo News report notes, another current shortcoming in the ECA is the leeway it gives states regarding the slates of electors they could send to Congress, potentially giving states the ability to overturn results if their legislatures decide to do so:

At the state level, the ECA gives governors enormous power over the slate of electors sent to the Electoral College. As of now, there is room under the law for a state legislature to try to throw out the popular vote in its state by sending a competing slate of electors to Congress. If the governor signs off on that slate, then the law would dictate that those electors are the ones that are counted.

Matthew Seligman, a fellow at the Center for Private Law at Yale Law School, has said that the ECA could be updated to more plainly state when electors can be chosen.

In addition to pressuring his vice president to disregard the election’s outcome, Trump’s push to contest the 2020 results, coupled with GOP lawmakers’ assertions that there was something amiss about those results, spurred thousands of his supporters to storm the Capitol as the certification process was taking place on January 6, 2021.

How lawmakers plan to change the Electoral Count Act

Talks about ECA reforms are still in their early stages at the moment, though they have picked up support from both sides of the aisle. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell is among those who has signaled an openness to considering them, an indication that there could be sufficient Republican support for a measure to pass the upper chamber.

ECA changes could help close certain loopholes that Trump tried to capitalize on during the vote certification process in 2021, several of which the House Administration Committee pointed to in its recommendations for reforms.

One of these suggestions would be increasing the threshold of lawmakers needed for an objection to be registered. Instead of only requiring one House member and one senator to raise an objection, committee staff recommends increasing this threshold to one-third of the members in the House and the Senate. Additionally, staff suggests that the vice president only have a very limited role in the process — including opening and presenting the electoral counts, but not presiding over the counting as they have in the past.

“There’s a good win there,” Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) previously told reporters when asked about potential changes. “I mean, my goodness, that’s what caused the insurrection.”

But there’s a lot the proposed updates wouldn’t accomplish.

Reforms to the ECA wouldn’t address pressure campaigns the former president launched in places like Georgia and Arizona, where he and allies urged election officials to ignore the electoral outcomes. (Trump could face charges for trying to interfere in the Georgia election.)

ECA reforms also wouldn’t combat a new Georgia law that enables the state election board to suspend local election officials, or the initial refusal of two Wayne County, Michigan, election canvassers to certify the region’s results in 2020 (both officials ended up reversing course). And it wouldn’t curb audits by states like Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, which have forced partisan reviews of election results that undercut trust in the outcome.

“One of the concerns is that states are taking steps to change state processes and authorities for certifying elections,” said Professor Rebecca Green, a co-director of the election law program at William and Mary Law School. “Electoral Count Act reforms would not touch those internal state processes, which are the domain of states and state legislatures.”

In addition to the limited role it can play in fighting election subversion, these reforms also offer no new protections for voters in states like Georgia, Texas, and Arizona, which have all recently passed laws intended to restrict access to the ballot by banning things like drive-through voting and shortening the time frame for submitting mail-in ballots.

Changes to the ECA “don’t do anything to block the suppression that’s taking place,” said Cliff Albright, a co-founder of the advocacy group Black Voters Matter. “They don’t block the attacks on drop boxes, on vote-by-mail, the criminalizing of people who give out food and water. They don’t block any of that.”

There’s another potential issue with the ECA reforms currently under discussion as well. Albright notes that the reforms could actually inadvertently enable election subversion if they make it harder for lawmakers to contest state results should state officials submit partisan results that do not match up with the actual outcome.

“Let’s say we have nefarious state officials. If you raise the threshold that you need [for objections], you certainly make it harder to smoke out that kind of nefarious problem with the election officials,” said Hamline University political science professor David Schultz.

Changes to the ECA are indicative of the watered-down policies Democrats will have to consider

Whether any ECA changes actually materialize is an open question. In the past, Republicans have signaled interest in policies, only for talks to falter when there’s been disagreement on key provisions. In the case of a 2020 and 2021 push for police reform, for example, Republicans expressed interest in a bipartisan compromise, but talks collapsed after members of both parties couldn’t overcome their differences on the issue of qualified immunity. The same dynamic has played out on gun control, which has garnered bipartisan support that’s failed to translate to concrete policies.

On the issue of voting rights more specifically, Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) has said she’d be open to working on a more limited measure that addresses voter protections and has previously voted in favor of advancing the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. There aren’t yet the 10 necessary Republican votes needed to actually pass a bill on that front yet either.

That means the ECA reform may be all Democrats are able to accomplish on elections in the near term, making it an example of how Democrats have to settle, since conservative members of their caucus have voted to preserve the filibuster. Because of Senate rules, Democrats will have to water down their proposals on everything from immigration reform to the minimum wage in order to have a shot of picking up any Republican support.

For now, the changes to the ECA seem like the most tenable election reform that lawmakers at the federal level may be able to achieve. Because of the narrow majority they have and the existing Senate rules, Democrats will likely need to make similarly drastic concessions on other priorities if they want to get anything done.

Russia’s invasion threat looms, and there have been no diplomatic breakthroughs yet.

“My guess is he will move in. He has to do something,” President Joe Biden said of Russian President Vladimir Putin during a Wednesday press conference. Biden was describing the predicament his counterpart has created for himself in Eastern Europe, as Russia has stationed tens of thousands of troops along the Ukrainian border.

Biden added that there is space to work with Russia on a peaceful solution if Putin wants it, but if he escalates, “I think it will hurt him badly.”

It was a remarkably blunt — maybe too blunt — assessment of the standoff between Russia and the West over Ukraine, which is staring down the threat of a possible Russian invasion. The crisis has built and built, lately with renewed signs of Russian aggression, from cyberattacks on Ukrainian government websites to the Kremlin moving troops to neighboring Belarus for joint military exercises. Against this backdrop, diplomatic talks in Geneva between the US and Russia sputtered earlier this month, and renewed efforts between US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on Friday produced no big breakthroughs.

Blinken said Friday that the two would speak again after the US consults with its allies and responds to a series of demands from Russia. It’s one sign there might still be a way out of the crisis, if not exactly an optimistic one.

Some of the big-ticket demands on Russia’s list are nonstarters with US and NATO allies, something Russia also probably knows. For example, Moscow wants guarantees that NATO would not expand eastward, including to Ukraine, and a rolling back of troop deployment to some former Soviet states, which would turn back the clock decades on Europe’s security and geopolitical alignment. These demands are “a Russian attempt, not only to secure his interest in Ukraine, but essentially re-litigate the security architecture in Europe,” said Michael Kofman, research director in the Russia studies program at CNACNA, a research and analysis organization in Arlington, Virginia.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23183594/russia_ukraine_map_1.jpg)

In other words, this is about Ukraine. But Ukraine is also a stage for Russia’s own insecurities about its place in Europe and the world, and how Putin’s legacy is tied up all in that.

“For Russia, what it sees as Western encroachment into Ukraine is a very big part of how the West has been weakening Russia, and infringing on a security interest for all of this time,” said Olga Oliker, program director for Europe and Central Asia at the International Crisis Group.

All of this makes it difficult to see a diplomatic way out, especially when 100,000 troops are posted along the Ukrainian border. Russia has denied that it has plans to invade, and few believe Putin has fully made up his mind on what he wants to do. But with all the threats and ultimatums, Putin may still have to do something if he cannot wrest concessions from the West.

“In a certain way, [he] has put himself in a corner,” said Natia Seskuria, associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute. “Because he can only do this once.”

Diplomacy isn’t totally dead. But it’s not going great.

Russia presented the United States with its demands last month. It requested “legally binding security guarantees,” including a stop to eastward NATO expansion, which would exclude Ukraine from ever joining, and that NATO would not deploy troops or conduct military activities in countries that joined the alliance after 1997, which includes Poland and former Soviet states in the Baltics.

Kyiv and NATO have grown closer over the last decade-plus, and actively cooperate. But Ukraine is nowhere close to officially joining NATO, something the US openly admits, and something Russia also knows. Still, NATO says Ukrainian future membership is a possibility because of its open- door policy, which says each country can freely choose its own security arrangements. To bar Ukrainian ascension would effectively give Russia a veto on NATO membership and cooperation. Removing NATO’s military presence on the alliance’s eastern flank would restore Russia’s influence over European security, remaking it into something a bit more Cold War-esque.

Russia almost certainly knew that the US and NATO would never go for this. The question is what Putin thought he had to gain by making an impossible opening bid. Some see it as a way to justify invasion, blaming the United States for the implosion of any talks. “This is a tried-and-true Russian tactic of using diplomacy to say that they’re the good guys, in spite of their maximalist demands, that [they’re] able to go to their people and say, ‘look, we tried everything. The West is a security threat, and so this is why we’re taking these actions,’” said David Salvo, deputy director of the Alliance for Securing Democracy and a senior fellow at the German Marshall Fund.

On the other hand, Russia’s hardline requests — alongside its aggressive military buildup — may be intended to get the West to move on something. “I don’t think that this was intended by Putin to fail, as some think. I think it was intended to extract concessions,” said Anatol Lieven, senior research fellow at the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. “And the question, of course, would be just how many concessions would satisfy the Russian government and obviously allow Putin to build up his domestic prestige.”

And that really is the question, especially since, so far, nothing seems to have really worked. Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman, a seasoned negotiator, met with Russian counterparts in Geneva earlier in January but made little progress. Blinken and Lavrov met Friday for 90 minutes; the meeting yielded no breakthroughs but Russia and the US agreed to potentially keep at it, after the US delivers written answers to Russia’s demands next week. “I can’t say whether or not we are on the right path,” Lavrov told reporters, according to the New York Times. “We will understand this when we get the American response on paper to all the points in our proposals.”

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23186308/GettyImages_1237876724.jpg) Russian Foreign Ministry/TASS via Getty Images

Russian Foreign Ministry/TASS via Getty Images

Russia might not like the responses on NATO, but there are spaces where the US and NATO could offer concessions, such as greater transparency about military maneuvers and exercises, or more discussions on arms control, including reviving a version of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, or even scaling back some US naval exercises in places like the Black Sea, which Russia sees as a provocation. “There is still potentially room on those fronts,” said Alyssa Demus, senior policy analyst at the Rand Corporation. “That’s entirely possible that the US and Russia or NATO and Russia could negotiate on those — and then maybe table the other issues for a later date.”

But if the US and NATO extend those olive branches or others, that might not be enough for Putin. Neither of these will resolve Putin’s fundamental sticking point. He has repeatedly framed the US and NATO as a major security threat to Russia for his domestic audience, including spreading disinformation about the West being behind the real chaos in Ukraine. “Having built up this formidable force, and issued all manner of ominous warnings, he’s got to come back with something tangible,” said Rajan Menon, director of the grand strategy program at Defense Priorities.

Moscow will likely continue the diplomatic route for as long as it thinks it serves its interests. But Russia has previously said it wouldn’t “wait forever.” “If they decide that it’s not worth continuing to talk — that they’re not going to get enough of what they want from talking — then they might as well fight,” Oliker said. “Then they’re doing it because they think the fight is going to get them closer to that solution than not fighting.”

Russia could opt to destabilize Ukraine — but it’s already been doing that

Russia has deployed troops, tanks, and artillery near the Ukrainian border, movements that look as though Moscow is preparing for war. But what kind of war will determine the humanitarian, political, and economic tolls, and the response of Ukraine, the United States, and Europe.

And, really, Ukraine is already at war. In 2014, Russia illegally annexed Crimea, and exploited protests in the Donbas region, in eastern Ukraine, backing and arming pro-Russian separatists. Russia denied its direct involvement, but military units of “little green men” — soldiers in uniform but without insignia — moved into the region with equipment. More than 14,000 people have died in the conflict, which ebbs and flows, though Moscow has fueled the unrest since. Russia has also continued to destabilize and undermine Ukraine, including by launching cyberattacks on critical infrastructure and conducting disinformation campaigns.

It is possible that Moscow takes aggressive steps — escalating its proxy war, launching sweeping disinformation campaigns and cyberattacks, and applying pressure in all sorts of ways that don’t involve moving Russian troops across the border and won’t invite the most crushing consequences.

But this route looks a lot like what Russia has already been doing, and it hasn’t gotten Moscow closer to its objectives. “How much more can you destabilize? It doesn’t seem to have had a massive damaging impact on Ukraine’s pursuit of democracy, or even its tilt toward the west,” said Margarita Konaev, associate director of analysis and research fellow at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET).

And that might prompt Moscow to see force as the solution.

What happens if Russia invades

There are plenty of scenarios mapping out a Russian invasion, from sending troops into the breakaway regions in eastern Ukraine to seizing strategic regions and blockading Ukraine’s access to waterways, to a full-on war with Moscow marching on Kyiv in an attempt to retake the entire country. What Russia does, ultimately, will depend on what it thinks will give it the best chance of getting what it wants from Ukraine, or the West. Any of it could be devastating, though the more expansive the operation, the more catastrophic.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23186318/GettyImages_1237852955.jpg) Anatolii Stepanov/AFP via Getty Images

Anatolii Stepanov/AFP via Getty Images

A full-on invasion to seize all of Ukraine would be something like Europe hasn’t seen in decades. It could involve urban warfare, including on the streets of Kyiv, and airstrikes on urban centers. It would cause astounding humanitarian consequences, including a refugee crisis. Konaev noted that all urban warfare is harsh, but the specifics of how Russia fights in urban settings — witnessed in places like Syria — has been “particularly devastating, with very little regard for civilian protection.”

The colossal scale of such an offensive also makes it the least likely, experts say, and it would carry tremendous costs for Russia. “I think Putin himself knows that the stakes are really high,” Seskuria, of RUSI, said. “That’s why I think a full-scale invasion is a riskier option for Moscow in terms of potential political and economic causes — but also due to the number of casualties. Because if we compare Ukraine in 2014 to the Ukrainian army and its capabilities right now, they are much more capable.” (Western training and arms sales have something to do with those increased capabilities, to be sure.)

Such an invasion would force Russia to move into areas that are bitterly hostile toward it. That increases the likelihood of a prolonged resistance (possibly even one backed by the US) — and an invasion could turn into an occupation. “The sad reality is that Russia could take as much of Ukraine as it wants, but it can’t hold it,” said Melinda Haring, deputy director of the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center.

Still, Russia could launch an invasion into parts of Ukraine — moving to secure more of the east, or south to the Black Sea. That would still be a dramatic escalation, but the fallout will depend on what it looks like and what Russia seeks to achieve. The United States and its allies have said that a large-scale invasion will be met with aggressive political and economic consequences, including potentially cutting Russia off from the global financial system to nixing the Russia-to-Germany Nord Stream 2 pipeline.

Biden, during his Wednesday remarks, said that if Russia invades it will be held accountable, though “it depends on what it does. It’s one thing if it’s a minor incursion and then we end up having to fight about what to do and not to do.”

Some accused Biden of signaling that Russia could get away with a baby invasion, though the White House later clarified that any move across the Ukrainian border will be met with “a swift, severe, and united response” from the US and its allies. Ukraine has said there is no such thing as a “minor incursion.” But those remarks also reflected the challenges of trying to contain Russia in a place the United States and Europe do not themselves want to fight, and where allies do have competing interests.

And Putin, of course, already knows this. “The question is,” Konaev said, “how much military power [Russia is] willing to commit to where it will call it a day and call it goals achieved?”

Has Putin backed himself into a corner?

Putin’s ultimatum — give me Ukraine, and a say in Europe, or I may do something with all these troops — is a dangerous one. Not just because, well, war, but because it has created a situation where Putin himself has to deliver. “He has two options,” said Olga Lautman, senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, “to say, ‘never mind, just kidding,’ which will show his weakness and shows that he was intimidated by US and Europe standing together — and that creates weakness for him at home and with countries he’s attempting influence.”

“Or he goes full forward with an attack,” she said. “At this point, we don’t know where it’s going, but the prospects are very grim.”