Trump Brings His Big Lie Playbook to the G.O.P. Primaries - Tuesday was a mixed bag for candidates endorsed by the former President, who is making fresh suggestions of election fraud. - link

Inside Putin’s Propaganda Machine - Current and former employees describe Russian state television as an army, one with a few generals and many foot soldiers who never question their orders. - link

The Problem with Blaming Robots for Taking Our Jobs - For decades, the effects of automation have been fiercely debated. Are we missing the bigger picture? - link

How Putin’s War Remade Washington - From a revitalization of NATO to the return of superpower nuclear anxiety, it’s been a breathtaking three months. - link

The Other Kind of Racism in Buffalo - Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor on the policies that excluded and impoverished the city’s Black population—long before last week’s shooting. - link

“Bright Star” manages to bottle the fleeting feeling of spring bliss.

Spring is glorious and terrible, especially in the Northeast United States. The first signs of flowers and greenery are so gorgeous and well-deserved after winter that a simple walk outside can feel positively giddy. There’s that vertiginous falling-in-love feeling that happens when the first actual not-cold breeze hits your skin. Then, just as you’ve taken a selfie with your spectacular neighborhood cherry blossoms, the petals flutter to the ground, and it’s over. Here in New York, the sidewalks heat up and reanimate the winter’s dormant dog pee, the city smells like garbage, and we have to wait a whole year to feel the ecstasy again.

If you wish there were a way to bottle the fleeting feeling of spring bliss like I do, I urge you to watch Bright Star, the Jane Campion film from 2009 about John Keats and his love, Fanny Brawne, played by Ben Whishaw and Abbie Cornish.

John Keats was an early 19th-century poet, now famed for being one of the greatest lyric poets in the English language. He was deeply inspired by William Shakespeare and Edmund Spenser, and he wrote odes and ballads like “Ode to a Nightingale” and “La Belle Dame sans Merci: A Ballad.” He died young and penniless of tuberculosis at age 25, and his work didn’t become famous until after his death. He fell in love with Fanny Brawne, an accomplished seamstress and nearby neighbor, but because of his financial situation, fragile health, and the general social mores of the Regency era, they couldn’t marry. He secretly gave her an engagement ring that she wore until her death, long after Keats had passed away and she married and had a family of her own (swoon!). It was during their love affair that Keats had his most prolific and inspired writing period, and it’s this three-year stretch — from meeting Brawne until his death — that is captured in the film.

Jane Campion’s hallmark is edgy, groundbreaking direction — she made the erotic thriller In the Cut before Bright Star — so a bonneted, empire-waisted costume drama doesn’t seem to promise the exciting filmmaking she is known for. But this is not a Jane Austen story where somehow everyone manages to get married at the end. Keats and Brawne’s love isn’t almost doomed; it’s actually doomed. All that makes its flame burn all the brighter, especially against the insanely gorgeous natural backdrop of this movie. Natural beauty was one of Keats’ strongest inspirations, and it’s clear that Campion took this to heart. The spring love sequences are some of the closest scenes I’ve seen on film to accurately capturing the sensation of being totally blissed out.

There’s Keats, gangly and tousled, scrambling barefoot up the rough trunk of a blooming apple tree to find a nightingale nest, the prickly bark and branches swaying under his weight until he finds a perch to close his eyes and dream (and get inspiration for one of his masterpieces).

There’s Brawne, reading a missive from Keats in an endless field of bluebells, so overwhelmed by joy that she grabs her little sister, Toots, and plants ferocious kisses all over her forehead.

There’s Brawne again, making her siblings go out and capture butterflies because Keats had written: “I almost wish we were butterflies and liv’d but three summer days — three such days with you I could fill with more delight than 50 common years could ever contain.” She lays in her sunny bedroom dizzily re-reading his letters as the insects flutter on her fingers.

And then there’s the first kiss between the lovers, on a moist forest floor, filled with so much sweetness, sensuality, and anticipation that my heart rate goes up every time. The soundtrack is nothing but birdsong, and you can hear the shifting of their bodies on the earth and the touch of their lips.

I can’t remember when I saw this film for the first time, but it quickly became a repeat watch. There’s a quality to this film that I haven’t seen anywhere else and that I have come to crave when seeking a certain feeling. Keats coined a term, “negative capability,” that he used often in his letters. He defined it as “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” In an interview about the making of the film, Campion says that “negative capability” became a guide to the creative process. You can see how that approach extends from the actors’ performances to the story itself. It’s as if Keats and Brawne are whispering to us from the past: We don’t know how long we have on this Earth, but it’s worth it to express and enjoy as much love and beauty as we possibly can.

Spring doesn’t last forever, not even in the film. There’s grief, longing, and dead butterflies swept into a dustbin. It’s an exquisite, brief time that fades much too soon, but the film reminds us that it’s worth succumbing to the beauty completely.

I don’t know how many people have seen this movie, but by my scientific estimation, it’s not enough. I just went back and read a bunch of reviews and learned that a few critics at the screening in Cannes were huffy because some of the plants depicted were in the wrong season for the story, and some butterflies were species that can’t be found in England. Ignore them. They’re just irritably reaching for fact and reason. Watch this film. Then take off your shoes and go climb a tree.

Bright Star is available to purchase on DVD. For more recommendations from the world of culture, check out the One Good Thing archives.

The FDA made a reasonable decision — but one that still shows much of what’s wrong with our current system for emergency approvals.

Last year, researchers who were testing cheap generic drugs in the hope that one or more of them might prove to work as a Covid-19 treatment stumbled across a promising candidate: the antidepressant fluvoxamine.

In a massive randomized controlled trial, called Together, researchers at McMaster University compared eight different repurposed drugs, and found most of them — including ivermectin, the antiparasitic that many embraced as a Covid-19 miracle cure — failed to do much against the disease. But fluvoxamine appeared to reduce severe disease by about 30 percent. While fluvoxamine had already shown some promise in small-scale trials last year, small-scale trials can sometimes turn up spurious good results, so most people didn’t take fluvoxamine seriously until the impressive data from the Together trial.

“This already feels different from hydroxychloroquine and company given the high quality of the research,” Paul Sax argued in NEJM Journal Watch, which analyzes recent research. “We might finally be onto something.” Government regulators, though, remained more skeptical — in part because the regulatory system isn’t exactly designed for adding new indications for drugs that have already been approved by the FDA without a pharmaceutical company sponsoring them.

Another researcher who was convinced of the case for fluvoxamine, David Boulware, decided to take matters into his own hands. The FDA didn’t know how to deal with submissions for a drug to be approved for a new indication without someone responsible for the submission? Fine. He’d submit it himself. In December, he wrote and submitted an emergency use application for fluvoxamine as a treatment for Covid-19.

In a lot of ways, it was a heartwarming story about the power of citizen science. But that’s not how it turned out.

This week, the FDA rejected the application for an emergency use authorization of fluvoxamine. Regulators argued that the results from the Together trial were more ambiguous than they looked — most of the benefits came from a reduction in extended observation in the emergency room, an endpoint fairly specific to the study’s clinical setting in Brazil and not necessarily all that useful. They pointed out that since the Together trial, additional studies have attempted to find a record of fluvoxamine’s benefits, and mostly haven’t found results as large.

In an unusual step, the FDA released an explanation for the rejection, and for the most part it’s very reasonable. But the whole episode still showcases what’s broken about how we review and approve drugs.

For eight months, the National Institutes of Health, which maintains an up-to-date database of research findings on treatments for Covid-19, didn’t update the fluvoxamine page with any information on the new, promising studies. (The NIH states on that page today, as it has for the last year, that “There is insufficient evidence for the COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel (the Panel) to recommend either for or against the use of fluvoxamine for the treatment of COVID-19.”)

That frustrated researchers, especially this past winter as omicron cases started to grow and the best treatments for Covid-19, like Paxlovid, were not widely available. Many of them told me that with results like these, the FDA would approve a drug that had a pharmaceutical company backing it, and that what was working against fluvoxamine was what they considered its biggest upside: that it was cheap and well-known.

To be clear, fluvoxamine was already approved by the FDA — for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). That means doctors can prescribe it in any context they think is appropriate, and it’s frequently prescribed off-label for anxiety and depression. It could also be prescribed off-label for Covid-19, but many doctors aren’t willing to do such off-label prescriptions. For that reason, the drug’s advocates wanted the FDA to determine that fluvoxamine is additionally indicated for Covid-19, so that treatment for the disease would be officially added to its listed uses alongside OCD. But many experts were skeptical.

“I don’t think the FDA ever will approve it for Covid,” Eric Lenze, the co-author of some early research on fluvoxamine, told me in December. “The reason the FDA will never approve it for Covid is exactly the reason it’s so useful for Covid; namely, it’s cheap and it’s widely available. No one can make any money off it, so no one is going to spend the money to appeal to the FDA to approve it.”

“The guidelines are overly conservative in that they have not yet endorsed fluvoxamine,” Ed Mills, one of the lead researchers of the Together trial, told me in November. Why was the FDA not giving fluvoxamine the same review it would give other drugs? “They don’t know how to deal with submissions where there isn’t someone to be responsible for it,” Mills said. The process of adding an indication is generally initiated by the drug developer, whose lobbyists work closely with the FDA to make sure they’re submitting the evidence the FDA wants to see for approval.

Fluvoxamine research had been largely funded through Fast Grants, a private philanthropic effort to make Covid-19 research work happen, and as the drug is generic, no one would make money from its approval for Covid-19. “It’s very disappointing as a scientist to see that it’s actually not about clinical evidence, it’s about lobbying,” Mills told me.

The FDA’s rejection notice this week made their thinking clear, and it’s clearly not purely about lobbying.

It’s important to note that the crucial justification for fluvoxamine as a treatment is much weaker now than it was this winter when Boulware filed the application. At the time, there was a serious dearth of effective Covid-19 treatments that could be taken at home rather than in the hospital. Monoclonal antibodies, the first line of treatment in earlier waves of the pandemic, weren’t working well against omicron. Many other therapies were only recommended for hospitalized patients. There was no simple pill a person could take at home while their case was mild to prevent progression into severe disease.

Today, there is: antiviral drug Paxlovid. Even fluvoxamine’s strongest advocates agree that Paxlovid works a lot better — it appears to reduce severe disease by 80 to 90 percent. And while this winter Paxlovid was scarce, today there are plenty of doses in the US — though many sick Americans still have trouble accessing the drug because of a lack of primary care doctors they can talk to, while too many doctors remain misinformed about when to prescribe it.

But Paxlovid isn’t a panacea, and it’d still be good to have more options in our portfolio. “There are effective therapeutics that are available. But not everyone has access to them. Not everyone can tolerate them. Some people have contraindications,” Boulware argued in response to the FDA rejection. “And if you go elsewhere in the world, low- and middle-income countries, they have access to no therapeutics.” Still, that Paxlovid, which is a significantly better option, is now widely available weakens the case for fluvoxamine in the US, even though countries that don’t have Paxlovid access should likely make their own calculus.

On the whole, then, the FDA’s decision to decline the EUA for fluvoxamine seems reasonable — even to me, a person who has been enthusiastic about the research supporting fluvoxamine. However, the decision still highlights a lot that should be improved about how the FDA makes and communicates decisions about Covid-19 treatment.

For much of the pandemic, if you tested positive for Covid-19, the advice from public health authorities was to do nothing unless your symptoms worsened. Until recently, the official CDC page about what to do if sick with Covid-19 only advised you to wear a mask, wash your hands, and clean high-touch surfaces to avoid infecting those around you. If your breathing deteriorates or you show signs of severe illness like confusion or an inability to stay awake, the CDC advises you to go to the hospital.

Recently, the CDC added an info box highlighting that if you are at high risk of severe disease, treatment may be available. But for people who aren’t categorized as high-risk — which includes older adults or those with medical conditions — the recommendations still don’t include any treatment options.

At first, the lack of treatment recommendations was likely because the evidence for any treatment option was pretty weak. Early in the pandemic, treatments like hydroxychloroquine were hyped but turned out not to work. Later, ivermectin was embraced as a miracle cure. (It isn’t.)

But the lack of treatment options was also the product of a process that wasn’t very good at identifying them and communicating that information to a confused public. The fluvoxamine clinical trial — and many other clinical trials of prospective treatments — was funded by private philanthropy because government processes were too slow to rely on. NIH official recommendation pages meant to summarize the state of research for various treatments were often months out of date; I wrote in November 2021 that the fluvoxamine page had last seen an update in the previous April.

And instead of the FDA proactively working with researchers to set up clinical trials the agency would be willing to rely on to recommend or disrecommend drugs, researchers had to design and conduct trials themselves, and then some doctors had to fill out the EUA application to get the FDA to look at the work they’d done.

Right now, the need for fluvoxamine is limited, the evidence is mixed, and the FDA’s decision not to recommend the drug is pretty reasonable. But ideally, the FDA would have been actively involved in the research process as soon as fluvoxamine first showed promise, and the government would have participated in designing and funding more definitive trials instead of waiting for a submission from an interested group of citizens.

The fact that the evidence about fluvoxamine is still inconclusive at this point is a good reason not to issue an EUA — but it’s also a sign of a glaring failure in our system for investigating promising Covid-19 treatments. Covid-19 is going to be with us for a long time, and other pandemics might be on the horizon. The process for developing treatments — and communicating with the public about them — needs to get better.

Experts are cautiously concerned, but this is a fundamentally different outbreak.

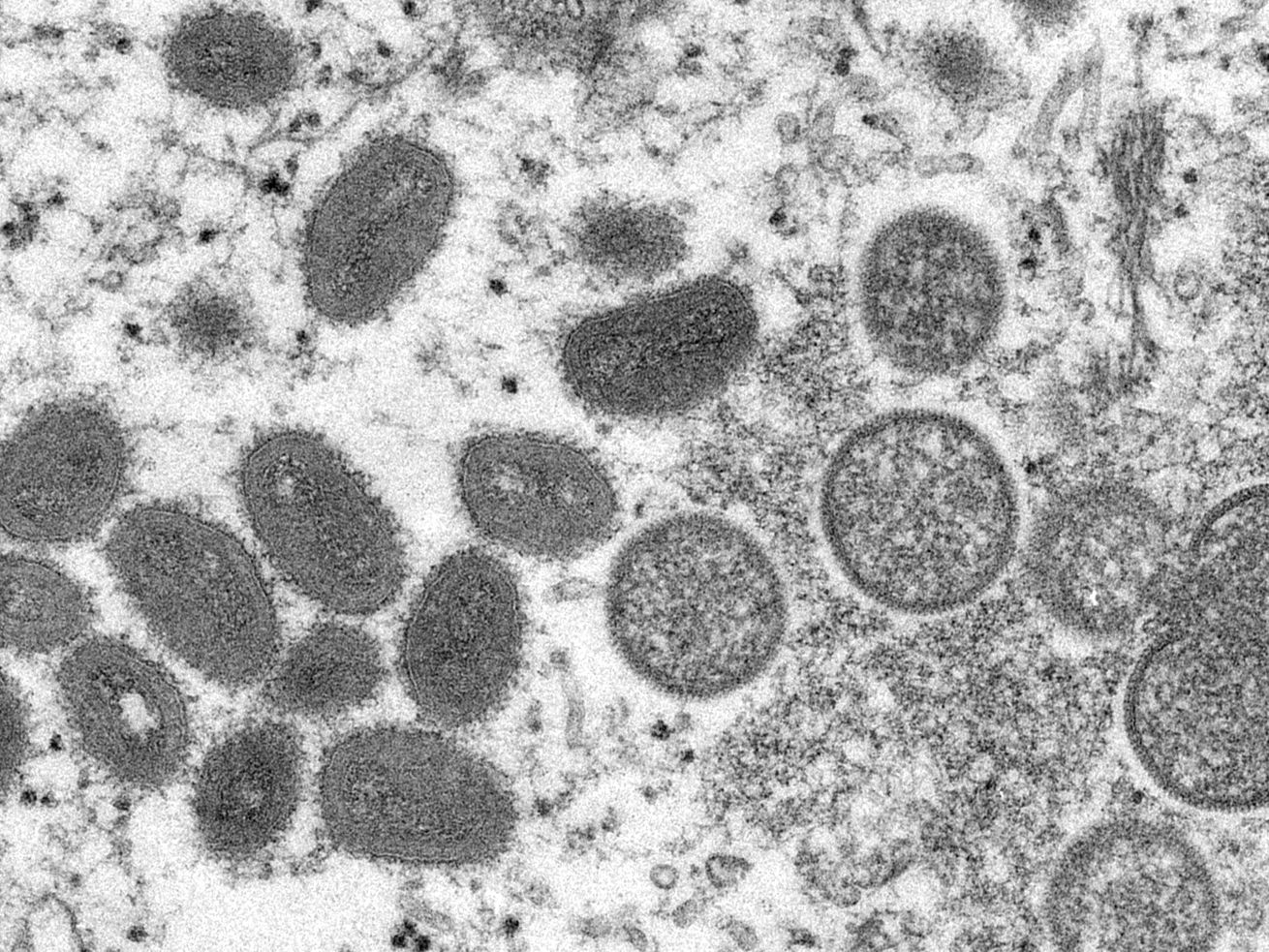

On Wednesday, the CDC confirmed a case of monkeypox in a Massachusetts man who had recently traveled to Canada.

It wasn’t the first time the US has seen a case of monkeypox, a virus related to smallpox that causes flu-like symptoms and a rash, and can sometimes be deadly. Occasionally, public health authorities identify single cases in people recently returned from West or Central Africa, where the disease is more common.

What’s different — and concerning — about this Massachusetts case is that it’s occurring as clusters of monkeypox infections are popping up in other countries where the virus is also rare.

Since early May, the UK Health Security Agency has detected a total of 9 cases of the infection, and Portugal and Spain have reported 14 and 23 suspected cases, respectively. (The numbers are changing rapidly; a University of Oxford epidemiologist tweeted a link to a makeshift tracker where you can see the latest figures.)

With so many monkeypox cases concurrently popping up in different countries, public health officials’ immediate questions are whether the cases are related, and whether monkeypox is spreading in other communities undetected.

“The worldwide concern from public health authorities is trying to understand how these are related to each other and what the causes are,” said Agam Rao, an infectious disease specialist and poxvirus expert at the CDC.

Only weeks into this outbreak, it’s too early to tell what exactly is going on, and whether this outbreak has epidemic potential. For the time being, said Rao, the general public doesn’t need to be particularly worried. “The risk is still very rare,” she said, and the strain of monkeypox currently being detected is relatively mild.

Two years into a deeply divisive global pandemic, word of another pathogen spreading unchecked might make some people want to launch themselves directly into the sun.

But with monkeypox, the world faces a very different situation than in the early days of Covid-19.

Monkeypox, unlike SARS-CoV-2, is a known quantity. We have more tools to prevent and treat it — far more than we did for Covid-19 at the outset of the pandemic — and both public health and the general public have had a lot of practice taking measures to prevent infections from spreading. Still, the trajectory of the outbreak is as yet uncertain, and public health experts remain vigilant.

Monkeypox viruses generally circulate among wild animals in Central and West Africa, and usually spread to people when they eat or have other close contact with infected animals. The virus was first identified among research animals at the CDC in the 1950s (that’s how it got its name “monkeypox”), and for a long time afterward, human infections were sporadic, even in countries where lots of animals are infected.

That’s partly because monkeypox is related to the smallpox virus, and immunity to smallpox is protective against monkeypox. But as of 1980, smallpox has been eradicated in humans, and vaccinations against smallpox have grown rare — and human cases of monkeypox have been on the rise. It’s still rare: According to the CDC, Nigeria has reported 450 cases since

2017, when public health authorities began seeing more cases among humans.

Infection with the monkeypox virus usually causes a flu-like illness with fever, headache, muscle aches, swollen lymph nodes, and a rash. Although monkeypox is not related to chickenpox, the characteristic monkeypox rash looks a lot like it, starting as red spots on the mouth and face, then spreading to the arms and legs. Over four to five days, the spots turn into small fluid-filled blisters that are often tender to the touch, eventually become doughnut- shaped, and begin to crust over by the two-week mark.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23575738/GettyImages_909695428t.jpg) Smith Collection/Gado via Getty Images

Smith Collection/Gado via Getty Images

Studies have suggested the virus’s R0 — the number of people who will hypothetically contract a communicable disease from a person infected with that disease — is relatively low, somewhere between one and two.

“It’s not as highly transmissible as something like smallpox, or measles, or certainly not Covid,” said Anne Rimoin, an infectious disease epidemiologist at the University of California Los Angeles with expertise in monkeypox and other emerging diseases.

Transmission can occur through close contact with body fluids of an infected person, sores, or items that have touched fluids or sores (like bedding); the virus can also spread via respiratory droplets or aerosols that linger in the air. But unlike Covid-19, where people who are infected can spread the disease before getting sick, monkeypox isn’t considered contagious before people develop symptoms.

There are two predominant strains of monkeypox: the “West African” version and the “Congo Basin” version. Of the two, the Congo Basin version has historically spread more easily from person-to-person and caused more deaths. The current outbreak involves the West African version.

The infection does not commonly lead to deaths in high-resource countries like the United States because people living there generally have better access to the supportive care that resolves most monkeypox infections, said Rimoin. In 2003, at least 53 people in the midwestern United States caught the infection from pet prairie dogs who’d been infected when they were housed near rodents imported from Ghana; none of the infected people died.

In rural parts of Africa, where access to hospital care is lower, infection has led to death in about 4 percent of people infected with the virus.

Several treatments approved for smallpox treatment could potentially be used to treat monkeypox infections if necessary. However, most cases are relatively mild; it’s unclear whether any of the currently affected patients needed or received any of these medications.

The latest clusters of monkeypox cases are different from previous clusters in a few ways.

For starters, the current cluster involves many infections happening concurrently beyond the African countries where the disease circulates in wild animals. “We’ve never had a situation where so many cases have occurred outside of those countries concurrently,” said Rao.

What’s also unusual about the latest cases is that many of them so far have occurred among men who have sex with men (monkeypox transmission has not previously been associated with sexual preference or intimate contact). Many of the cases are presenting with clusters of pimple-like spots in the genital area — an uncommon area for the monkeypox rash to start.

After clinicians made the first few diagnoses among men coming to sexual health clinics with unusual rashes, health officials began asking sexual health clinics to look out for monkeypox cases. This doesn’t mean monkeypox is only circulating among men who have sex with men, and some infections have been diagnosed in people who are not gay or bisexual men.

“We’re finding where we’re looking,” Maria Van Kerkhove, a World Health Organization emerging diseases and zoonoses expert, said in an interview with STAT.

If this monkeypox outbreak does end up linked to sexual networks among men, that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a sexually transmitted infection; it may simply be a question of who’s getting close enough to an infected person to get infected, themselves. Other germs spread by close — but not specifically sexual — contact have previously caused clusters of infections among gay and bisexual men and college-aged students, such as meningitis, a disease spread by respiratory droplets in close settings.

In addition to trying to understand the cause of the current outbreak and the routes of transmission, public health authorities are working to sequence the viruses isolated from individual patients to better understand whether it has changed in any ways that might make it more or differently transmissible, said Rao.

For the moment, however, there’s no reason to think the virus has undergone any meaningful mutation, she said.

Currently, the general public doesn’t need to be particularly worried about the risk monkeypox viruses pose to themselves and their loved ones. “It does not spread easily from person to person, the risk to the general public is low,” said Rimoin. And with health providers now on high alert for the infection, it is more likely to be recognized quickly among people who do get infected and quickly contained, halting chains of transmission.

“We’d have to see a significant cluster of cases events and ongoing transmission” before public health authorities put any broad preventive measures in place, said Rimoin.

Even a large monkeypox outbreak would likely be much easier to handle than the Covid-19 pandemic. For one, the fact the virus isn’t considered contagious before people show symptoms could make it harder for people to unknowingly spread it. And in addition to treatments, we already have excellent vaccines to protect those at highest risk from infection — public health authorities in the UK are currently vaccinating close contacts of cases to prevent further spread of infection.

This isn’t a novel disease — so if monkeypox does become a much larger outbreak than it already is, public health authorities are better equipped with tools to manage it.

In fact, as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic, public health is in a relatively strong place to handle this outbreak.

“I think we’re in a good position to respond to monkeypox because most health departments have staffing, lab networks, and funding from Covid that can be used for emergency response,” said Jay Varma, a physician and epidemiologist based in New York City who recently was senior advisor to the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The real risk is what happens when that funding runs out over the next few years.”

Borussia Dortmund sacks Marco Rose after just one season as coach - Borussia Dortmund has dismissed coach Marco Rose after what the Bundesliga club called an “unsatisfactory” maiden season that yielded no trophies

Sindhu reaches Thailand Open semifinals by defeating Yamaguchi - P.V. Sindhu overcame world No. 1 Akane Yamaguchi 21-15, 20-22, 21-13 in the quarterfinals of the Thailand Open to set up a clash with Olympic champion Chen Yu Fei in the semifinals

A year on, Naomi Osaka's French Open exit blazes path for mental health discussion - Naomi Osaka had stunned the tennis world when she withdrew from the 2021 French Open after boycotting post-match media duties. A year, the sport is addressing the mental toll on athletes

Wild Emperor, Ballerina, Aracana, Multifaceted, Ravishing Form, and All Attractive excel -

IPL 2022 | Disappointed Mumbai Indians coach Jayawardene concedes team didn’t win crucial moments - Mumbai Indians are likely to end up last on the points table even if they manage to win their last game against Delhi Capitals

Expo to raise funds for ailing artist -

Kerala Tourism holds roadshows in Muscat, Manama - State presented as a ‘Paradise, Four Hours Away’

Congress targets PM over reports of China building second bridge over Pangong Tso - ‘… A timid and docile response won’t do. PM must defend the nation’, tweets Rahul Gandhi

DGCA grants Jet Airways air operator certificate, can resume commercial flight ops - The airline intends to restart commercial flight operations in the July-September quarter..

Over 4,000 black spots in Kerala’s road network, says NATPAC’s draft report - Multiple black spots on corridors to be treated as cluster

Ukraine war: US fully backs Sweden and Finland Nato bids, Biden says - Both countries submitted their applications to be part of the Western defence alliance this week.

Ukrainian widow confronts Russian soldier accused of killing her husband - The 21-year-old serviceman has pled guilty to killing her husband in a village in Ukraine’s north-east.

Russian McDonald’s buyer to rebrand restaurants - The fast food giant says the new owner of its 850 Russian restaurants will operate them under a new brand.

Monkeypox cases investigated in Europe, US, Canada and Australia - Cases of the rare disease are now confirmed in eight European countries, health authorities say.

Vangelis: Chariots of Fire and Blade Runner composer dies at 79 - The Greek star’s Oscar-winning film scores and electronic works created “a new musical landscape”.

Rocket Report: Starliner soars into orbit, About those Raptor RUDs in Texas - “From the outside, it might look like an ordinary rocket.” - link

Hyundai and Kia recall nearly 20,000 Ioniq 5s, EV6s - A voltage fluctuation could cause the cars to roll away when parked. - link

Texas looks to a Clarence Thomas opinion to defend its social media law - Thomas argued that social networks are like common carriers. - link

A time paradox births a “freaking Kugelblitz” in Umbrella Academy S3 trailer - Too many siblings and not enough timeline spells trouble in this Netflix series. - link

Multiversus hands-on: Finally, a compelling Smash Bros. clone - Yes, the Warner Bros. pastiche is weird. But its co-op arena battling is refined. - link

So a philosopher, a mathematician, and a physicist were at starbucks.

The mathematician turns to the physicist sitting next to him and says “You know, physics is just applied mathematics!”

They all have a good laugh, at which point the philosopher interjects from across the table. “And mathematics is just applied philosophy!”

The laughter roars even louder, and then the physicist turns to the philosopher.

“Shut the fuck up and make my coffee.”

submitted by /u/pradeep23

[link] [comments]

The devil welcomes him and says:“Let me show you around a little bit.” They walk through a nice park with green trees and the devil shows him a huge palace. “This is your house now, here are your keys.” The man is happy and thanks the devil. The devil says:“No need to say thank you, everyone gets a nice place to live in when they come down here!”

They continue walking through the nice park, flowers everywhere, and the devil shows the atheist a garage full of beautiful cars. “These are your cars now!” and hands the man all the car keys. Again, the atheist tries to thank the devil, but he only says “Everyone down here gets some cool cars! How would you drive around without having cars?”.

They walk on and the area gets even nicer. There are birds chirping, squirrels running around, kittens everywhere. They arrive at a fountain, where the most beautiful woman the atheist has ever seen sits on a bench. She looks at him and they instantly fall in love with each other. The man couldn´t be any happier. The devil says “Everyone gets to have their soulmate down here, we don´t want anyone to be lonely!”

As they walk on, the atheist notices a high fence. He peeks to the other side and is totally shocked. There are people in pools of lava, screaming in pain, while little devils run around and stab them with their tridents. Other devils are skinning people alive, heads are spiked, and many more terrible things are happening. A stench of sulfur is in the air.

Terrified, the man stumbles backwards, and asks the devil “What is going on there?” The devil just shrugs and says: “Those are the christians, I don´t know why, but they prefer it that way”

submitted by /u/fhqwhgadsz

[link] [comments]

The dog says, “Humans like us more. They even named a tooth (canine) after us. Naming such an important body part after us shows that they like us more.”

The cat smiles and says, “You’re not really going to win this one you know.”

submitted by /u/Majorpain2006

[link] [comments]

Nothing to do with my intelligence. I just go to sleep if left unattended for 15 minutes.

submitted by /u/thisisa_fake_account

[link] [comments]

I asked my 10 brothers and sisters, but they don’t know either.

submitted by /u/MEforgotUSERNAME

[link] [comments]