Every brain experiences reality differently. This census might help us understand why — and what it means.

For something as intimate to our lives as perception — how we experience ourselves and the world — we know remarkably little about all the ways it can differ from person to person. Some people, for instance, have aphantasia, which means they experience no mental imagery, while others have no inner monologue in their heads, just silence. Studying what scientists now call “perceptual diversity” is part of an increasingly mainstream effort to learn more about consciousness itself.

Among the new wave of researchers who are trying to unravel the mystery of consciousness in the lab is Anil Seth. Seth is the co-director of the Sackler Centre for Consciousness Science and the author of Being You: A New Science of Consciousness. His viral TED talk in 2017 popularized the idea of consciousness as a “controlled hallucination,” which suggests that our perceptions are less like looking through a transparent window on the outside world and more like watching an internally constructed movie. When sensory data from the outside world contradicts our brain’s movie, it updates the film.

Now Seth is behind another project that aims to “paint a multidimensional portrait of this hidden terrain of inner diversity,” he told me. By studying the subtle ways perception can vary, we can understand the many different ways our brains construct our realities. That’s why in 2022, Seth and his colleagues in collaboration with the creative studio Collective Act launched the Perception Census, the largest psychological study of its kind. It aims to help bridge the divide between philosophy and science by providing experimental evidence for questions, such as how our individual minds differ, that have long been out of reach.

The online survey gives participants a series of tasks, brain teasers, and interactive illusions that each probe a different aspect of perception, such as vision, sound, rhythm, how you experience the passage of time, and even how your imagination works. It’s already reached over 20,000 participants. “Just as biodiversity is important for the health of an ecosystem,” Seth told me, perceptual diversity “is something that enriches society.”

I spoke to Seth about what the perception census is, why perceptual diversity matters, and how this all relates to the growing field of consciousness studies.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What got you interested in a project like the Perception Census?

My research and [that of] many others has led to this view that what we perceive is not a direct readout of what’s there. It’s an active construction in which the brain plays an essential role. Because of the way perception works, it seems to us that we see the world and hear the world as it is — it doesn’t seem like it’s a brain-based construction. Unless you interrogate that, it’s very hard to understand that somebody might actually be having a different experience, even if they’re in the same shared objective reality.

And, of course, we all have slightly different brains. So we’re all going to inhabit different inner universes, and not a lot is known about that. With this idea of perceptual diversity, what we’re trying to do is bring back into the light this idea that, in fact, we all differ, and the differences don’t have to be very large to exist.

Is this the first time anyone has systematically studied the different ways we experience the world?

It’s definitely not the first time. There’s a long tradition of looking for individual differences. But what’s distinctive about what we’re doing is the scale, breadth, and reach.

[The Perception Census] has about 100 different things that people can do, each probing different aspects. That scale hasn’t been attempted before. That allows us to look at what the patterns are, and whether there are underlying factors that explain how different aspects of perception correlate.

Beyond intrinsic interest in learning more about consciousness, what could we do with a richer understanding of perceptual diversity?

One goal of the census is awareness-raising because people are remarkably surprised when they realize that people can have different inner experiences. But they’re also surprised just by all the under-the-hood complexity involved in this everyday miracle of just experiencing the world.

I also think it can cultivate a bit of useful humility about our own perceptions and beliefs. If we really had this understanding that the way I see things is not the way they are, then it’s easier to understand that somebody else might see something differently. In a world of increasing polarization and fragmentation, understanding that we differ, and how we differ, can build platforms for empathy and communication.

When it comes to mental health, neurodiversity is a well-established community with lots of important lobbying efforts that have done great work. But it tends to be associated with specific conditions and reinforces this normative, neurotypical view for people who aren’t neurodivergent in that way. What I’m hoping is that the census can reinforce the recognition of diversity in the normative, neurotypical range.

How do you imagine this kind of research could evolve in the future?

We can start to drill down. For instance, if we find some interesting aspects of perceptual diversity that stand out, or some factor that seems to predict diversity in different dimensions, then we might bring people into the lab. We can do more fine-grained controlled experiments, using things like brain imaging. We might begin to look at the biological mechanisms that are responsible for this diversity. We can’t do that in a large-scale survey.

Then we could also zoom out. There are limitations on what we’ve been doing. We’re only looking at people who speak English. We’re not really sampling across cultures as much as we would ideally like. Also just for very boring ethics reasons, we’re only looking at people 18 and over, so another whole range is what’s going on with the development of perceptual diversity; that can be new terrain, too.

And we’ve got 100 tasks, but that’s a small subset of the possible things we might want to ask. One of the things we were worried about was that we’re asking quite a lot of people to spend their precious attentional moments on something, so we have to make it rewarding for them. And it turns out, we have 20,000 people already, and one comment we received was that “this is what the internet is made for.”

In your book Being You: A New Science of Consciousness, you write that advances in the science of consciousness are “inaugurating a transformation in psychiatry from treating symptoms to addressing causes.” I’m curious how you think these kinds of advances might help support this transformation.

Many different things can catalyze that move. The census is, in itself, not telling us much about mechanisms. But it’s laying out the territory. By seeing what correlates with what, that will give us some indication of whether there are dials in the brain, if you like, that you can turn, and they change perception in different ways, or maybe if you turn it too far, you get something that can transmogrify into mental illness.

So you need to know the lay of the land in order to understand the kinds of mechanisms we’re looking for that may go awry in mental health disorders. More generally, consciousness research is making advances here.

Whether it’s psychedelics or computational psychiatry, there are increasingly detailed mechanistic proposals for why people have the psychiatric symptoms they do. The key thing that consciousness research brings to that is a focus on their experiences, rather than the behavioral symptoms of psychiatric and mental health disorders.

If you’d like to help chart the terrain of perceptual diversity, you can take the Perception Census here.

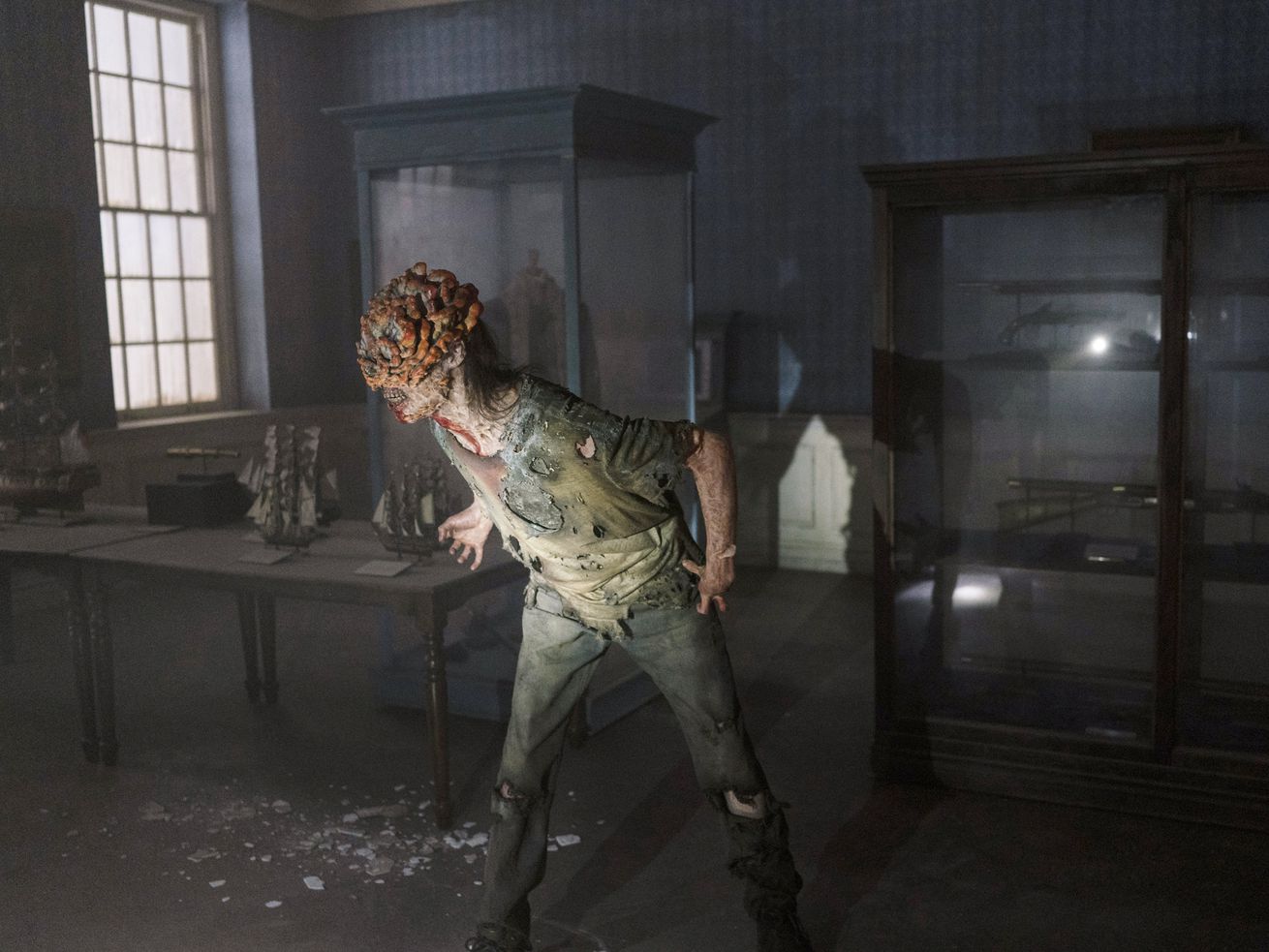

The Last of Us’ Cordyceps aren’t exactly real — but the lack of a vaccine to prevent them is.

The second episode of the HBO hit The Last Of Us opens with a scene in Jakarta, Indonesia. It’s set in 2003, at the beginning of a (fictional) fungal pandemic that goes on to destroy the world as we know it. After an expert in fungal biology evaluates the body of an infected factory worker, she speaks quietly to a military official who has asked for her help controlling the pathogen’s spread.

“There is no vaccine,” she says to his stricken face.

It was true in real-world 2003, and it’s true now: Although vaccines against bacterial and viral diseases abound, no vaccines against any fungal pathogens are licensed for human use.

It’s not for lack of trying: Dennis Dixon, who leads bacterial and fungal research at the National Institutes of Health, said there’s been “continuous activity” aimed at developing fungal vaccines for decades. But a variety of challenges both scientific and economic have conscripted even more promising fungal vaccine candidates to the pharmacologic dustbin — to the detriment of human health.

The zombie-causing fungus in the show is mostly fictitious — at least, as a human pathogen. In reality, most severe fungal infections in humans affect immunocompromised people, including people with untreated HIV infection and those receiving cancer treatment, organ transplants, or medications for autoimmune diseases. (These usually manifest as lung and bloodstream infections or meningitis, and not zombification.)

However, some affect people with normal immune systems — ever had a yeast infection, or heard of valley fever? — and the global burden of fungal infections is expected to increase as the number of people receiving immunosuppressive drugs continues its upward climb and climate change accelerates.

The urgency of finding a vaccine to prevent any fungal infection — or ideally, preventing multiple types of fungal infections with one vaccine — is not new, but it’s growing.

Which raises the question: Why, in the year of our lord 2023, do we still not have any fungal vaccines? The answers highlight challenges in both the science and economics of vaccine development — and some idiosyncrasies about a kingdom of life already known for its very specific (and highly telegenic) weirdness.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24421868/image.png)

A fungal vaccine would help prevent a lot of infections

Fungi are all around us: in the air we breathe, on the surfaces we touch, and all over the insides and the outsides of our bodies. Still, most of us are at low risk for fungal infections, as long as our immune systems are functioning normally.

The worst fungal infection likely to affect a person with a healthy immune system is probably one caused by a member of the Candida genus, which are technically yeasts (yes, yeasts are a type of fungus, as are mushrooms and molds). Vaginal yeast infections are an especially common form of candidal infection that often affects healthy people, leading to 1.4 million clinic visits a year in the US alone. Worldwide, an estimated 138 million women get four or more yeast infections a year. Other fungal infections common to healthy people include ringworm — which, surprise! isn’t caused by a worm at all — and infections of the nails on fingers or toes.

But fungal infections (including and beyond yeast infections) are a much bigger threat to people with compromised immune systems. Worldwide, fungi cause 13 million infections and 1.5 million deaths every year. And in 2018, treating these infections cost Americans nearly $7 billion.

Fungal infections are most common in immunosuppressed people. That complicates developing and deploying fungal vaccines.

The fact that the most severe fungal infections primarily affect immunosuppressed people creates some big challenges when it comes to developing vaccines to protect against them.

First of all, this makes it complicated to find participants for clinical trials testing fungal vaccines.

To determine whether a vaccine works, scientists need to test promising vaccine candidates — usually, prototypes that have successfully prevented the disease in experimentally infected animals —in large groups of humans. Because we live in a world with medical ethics, scientists can’t experimentally infect humans. Instead, they need to wait for people in the trial to naturally encounter the disease they’re trying to prevent.

The more rare that disease, the more people scientists need to follow (and for a longer time) to look for the disease. And while severe fungal infections are a growing problem, they’re still relatively uncommon.

Karen Norris, an immunologist at the University of Georgia’s veterinary school who leads a team developing a fungal vaccine candidate, said her team had “done the math” on the time it would take to study a hypothetical vaccine targeting a single fungal infection. “It’s doable, but it would take a couple of years to enroll that many patients,” she said.

It’s also hard to design vaccines that work for the immunocompromised people who need them the most. An effective vaccine works by training a person’s immune system to respond quickly to a certain germ — and suppressed immune systems are hard to safely train.

In some cases, it’s possible to predict immunosuppression — for example, when a person is preparing to receive chemotherapy or another immunosuppressive treatment. But not always: People with HIV and those who are born with immune system disorders can’t plan or predict the state of their immune systems.

That creates big challenges for scientists, who ideally want to develop vaccines that protect both people with healthy immune systems who go on to have immunosuppression, and those whose first diagnosis involves immunosuppression.

Another problem: Fungal cells have more similarities to human cells than do viruses or bacteria. That makes it more complicated to design a vaccine that trains the immune system to attack fungal cells without attacking our own cells.

The biggest barrier to fungal vaccines might be economic

Even if a vaccine is shown to be safe and effective in clinical trials, that doesn’t mean it will get to mass production and market: For that, it also needs to have the potential to make a profit. “The testing of a vaccine in this space is, to be honest, not that attractive to big pharma, etc., because they are not infections that occur at a high frequency in a lot of patients,” said Norris.

Even if a vaccine prevents a lot of illness and death in a group of people — and reduces the costs of their medical care — those benefits accrue to individuals and health care systems, not to the pharmaceutical companies who incur the costs of developing and producing the vaccine.

“It’s going to take someone to develop that tough market for this to go forward,” said Dixon. A viable vaccine will need to not only be effective at preventing disease, but effective at doing so in enough people to make producing the vaccine at scale a worthwhile investment for pharmaceutical companies.

Still, people are working on fungal vaccines, and there are a few promising candidates

Regardless of the obstacles, people are working to develop fungal vaccines — and have been for decades.

To overcome the economic inviability of developing vaccines that prevent only a small number of infections, several scientists are developing vaccines that prevent multiple fungal infections — or better yet, all of them.

Norris’s group has developed a prototype targeting three fungi responsible for 80 percent of all infections in immunocompromised people: Candida, Aspergillus, and Pneumocystis. The prototype significantly reduced illness and deaths due to these infections in experimental mice and primates. A wide variety of other candidates are also being studied.

Three fungal vaccines have made it into the human clinical trial stage to date. In the early 1980s, a trial of a vaccine to prevent infections with Coccidioides — the fungus that causes valley fever — didn’t reduce infections, and produced lots of side effects. More recently, two vaccines aimed at preventing Candida (i.e., yeast) infections had good results in human safety trials, one of which went on to show promise at preventing recurrent vaginal infections in a small, placebo-controlled trial. But without an investor to take testing to the next level — a clinical trial comparing the vaccine to standard preventive therapy — development stalled out, said Dixon.

Norris said additional animal safety studies of her team’s prototype could take another year. If those go well, the next step — a safety trial in humans — would also take about a year. After that, at least several more years of work await before her team has a licensed vaccine produced at scale.

So while any progress on fungal vaccines feels momentous, it’s wise to stay grounded about the timeline of progress in this space, said Dixon. “It’s certainly going to be a while to figure out how to get the science right, to get the protection right,” he said, “and get to the goal line.”

The big problem with Florida asking for so much of its student-athletes’ health information.

Last August, two months after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, parents in Florida’s Palm Beach County School District began raising questions about a rule requiring the state’s student-athletes to submit detailed medical history forms to their schools prior to sports participation.

For at least two decades, the forms have included a set of optional questions about students’ menstrual cycles. But now, with abortion criminalized in many states, there’s greater concern that menstrual data could be weaponized to identify or prosecute people who have terminated pregnancies. (In 2022, Florida passed a ban on abortions after 15 weeks, and its leadership has signaled interest in further restricting access to the procedure.)

And this school year, the Palm Beach County school district began offering students the option to submit the form via a third-party software product, leading to a particularly high level of alarm about data privacy.

Some district parents wanted the period questions gone. The episode also raised larger questions about whether any of the medical data collected by these forms should be held by a school or a district at all.

Over the course of several meetings, the Florida High School Athletic Association (FHSAA), which makes the rules governing student involvement in school sports statewide, leaned into a hardline position on both questions.

In January, the organization’s sports medicine committee recommended making the menstrual history questions mandatory and requiring students to turn their responses over to the school, according to the Palm Beach Post’s reporting.

Florida wasn’t the only state to ask student-athletes for their menstrual histories. In fact, a minority of states — only 10 — explicitly instruct student-athletes to keep menstrual information and other health data private.

Regardless, the proposal to require this information was extraordinarily hard to justify: It created privacy risks and defied the recommendations of national medical associations, and was at jarring odds with the state’s prevailing educational trends, which have prioritized parental rights over almost everything else.

In the end, the proposal failed after it attracted national scrutiny and prompted debates about what entities should have access to menstrual information. On February 9, the Florida High School Athletic Association voted to adopt a new medical evaluation form that does not include questions about menstrual history. Instead, students will submit an eligibility form that contains no medical details.

(Also on February 9, Florida Democratic Rep. Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick and two other representatives introduced federal legislation that would prohibit publicly funded schools from requiring students to report menstrual information.)

In a microcosm, the episode drives home a new reality of post-Roe America: Period data should only be shared between patients and their health care providers.

Periods are signifiers of health, and people should talk about them — with their clinicians

Menstrual cycles are such an important signifier of health that many health care providers call periods the “fifth vital sign.” In athletes in particular, period changes can signify a person isn’t getting enough calories to offset high levels of activity.

So yes, athletes with periods should watch and seek care for changes in their cycles, said Judy Simms-Cendan, a Miami-based pediatric and adolescent gynecologist and president-elect of the North American Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology.

“But the physician or clinician assessment of a menstrual history, and what it may or may not signify, is different than a school’s use of that information,” said Simms-Cendan. Coaches aren’t usually health care providers, so they’re not equipped to medically evaluate people based on menstrual symptoms. But also — and crucially — schools and sports programs are not required to keep health information private in accordance with federal HIPAA laws. (Schools are subject to other rules about sharing student data, but those rules permit access to data for a broader range of reasons than HIPAA does.)

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) publishes separate forms for medical providers to complete when evaluating an athlete prior to their participation in a sport. One form is just for the health care provider’s eyes: a physical evaluation form that includes a warning that it’s not to be shared with schools or sports organizations. Then there’s a separate eligibility form for the physician to share with the school, with much less room for detail.

The AAP keeps unnecessary medical details off the eligibility form for a reason, said Simms-Cendan. “That’s nobody’s business. You shouldn’t have to disclose it, because it doesn’t have anything to do with your sports activity,” she said.

Good arguments against (and no arguments for) sharing period information outside a clinician’s office

Parents’ fears around sharing their kids’ health data with schools are rightly grounded. Without HIPAA protection, disclosing health information can threaten individuals’ right to privacy.

Less scrupulous period-tracking apps also pose risks, as do some apps aimed at treating addiction disorders, depression, and HIV. In 2019, the director of the Missouri health department was caught using a period-tracking spreadsheet to identify patients who may have had “failed” abortions; there’s good reason to fear that an activist state government seeking to criminalize abortion would attempt to use period information tracked online in service of that goal.

It was unclear why the FHSAA’s sports medicine committee was so eager to have Florida schools gather menstrual data from the state’s student-athletes, or how they could use that data to discriminate against students.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis reportedly favors a near-total ban on abortion, and in 2021, he signed a bill barring transgender girls from playing on girls’ teams in public schools. Could the questions have been intended to identify and punish students who don’t conform to the state’s gender politics?

The questions — which ask about the date of menstrual onset and the timing and frequency of periods — wouldn’t have yielded the kind of data that would help identify teens seeking abortion services, using contraception, or getting evaluated for sexually transmitted infections. They would have been poor screening questions to identify transgender students.

(The new medical eligibility form has been revised to include a non-optional question indicating the student’s sex assigned at birth. According to the Palm Beach Post’s reporting, FHSAA staff have indicated the new form aligns with the 2021 law restricting transgender girls’ sports participation.)

Insisting on the menstruation questions’ inclusion over the objection of parents was also weirdly out of sync with the state’s Florida’s Parental Rights in Education bill, often called the “Don’t Say Gay” bill, said Simms-Cendan. “Our governor is incredibly supportive of parental control over student education,” and parents should also have the right to control and protect their children’s health information, she said.

“I really don’t know what they’re trying to get at by asking this information,” she said in an interview prior to the FHSAA’s decision to change the form.

Overall, Simms-Cendan thinks it’s “really positive” that more people are talking openly about periods. But it’s one thing to educate students about menstrual health, and another thing entirely to assess and analyze someone’s personal menstrual history outside of a health care setting.

Young people need to be aware of the risks that can arise when they lose control over that information, she said. “We call our reproductive health system ‘our privates’ for a reason.”

Update, February 10, 5:30 pm ET: This story was originally published on February 7 and has been updated to reflect that the Florida High School Athletic Association is dropping the requirement for students to share their menstrual histories and has revised the new medical eligibility form to include sex assigned at birth. Also added was information about proposed federal legislation to prohibit similar requirements in other public schools.