The Biggest Potential Water Disaster in the United States - In California, millions of residents and thousands of farmers depend on the Bay-Delta for fresh water—but they can’t agree on how to protect it. - link

As Gas Prices Reach New Highs, Oil Companies Are Profiteering - The Biden White House is confronting a form of shareholder capitalism that has no place for modest profits or rallying around Ukraine. - link

A Trump-Backed Candidate Faces Sexual-Assault Allegations in Nebraska - In the Republican primary for governor, the businessman Charles Herbster is accused of groping eight women, and is being challenged by two rivals. - link

DeafBlind Communities May Be Creating a New Language of Touch - Protactile began as a movement for autonomy and a system of tactile communication. Now, some linguists argue, it is becoming a language of its own. - link

What the “Life of the Mother” Might Mean in a Post-Roe America - “We are going to see more deaths and more injuries,” Ghazaleh Moayedi, an ob-gyn in Dallas, said. “I don’t have to speculate about that at all.” - link

The ocean has a roadkill problem.

The largest fish on Earth is a shark. Capable of reaching a length of up to 60 feet — roughly the height of a four-story building — whale sharks, named for their size, are so large that they make great whites look like minnows.

But even giants can disappear. Over the last several decades, more than half of all whale sharks have vanished from the ocean. Some populations have fallen by more than 60 percent.

This decline has been something of a scientific mystery. It can’t be explained by known threats like overfishing. And because whale sharks sink when they die, there aren’t bodies washing up on shore that researchers can study.

Now a new clue has emerged, and it’s a big one. A study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that cargo ships are likely a leading cause of whale shark deaths. Often, where you find high densities of these endangered fish, you also find shipping traffic, the authors found, and ships are already known to strike and kill these animals.

Our lives as consumers connect us to this seemingly far-away problem. More than 80 percent of all internationally traded products are carried by cargo vessels, such as TVs and cookware and whatever device you’re reading on now. And the world’s marine fleet is rapidly multiplying, growing from 1,771 large vessels in 1995 to more than 94,000 in 2020. The ocean is now full of highways packed with ships.

Whale sharks are not the only roadkill. Vast cargo vessels harm many species of marine giants, such as the endangered North Atlantic right whales, and some smaller creatures, like sea turtles. Ships also emit loud noises that disrupt marine life and spew planet-warming carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

“Shipping is a serious problem for giants of the sea,” said Robert Harcourt, a marine ecologist at Macquarie University in Australia who was not affiliated with the study. “We have an economy that’s derived from moving things around the world in a way that’s not taking into account the cost to the environment.”

Last fall, a large tanker painted red, white, and blue pulled into a harbor in southern Japan. Draped limply across its bow was a dead, 39-foot whale.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23454673/image.png) Mizushima Coast Guard Office

Mizushima Coast Guard Office

Tragic photos that document whale strikes are rare, but the strikes themselves aren’t. They affect at least 75 different species of marine animals, according to a recent review, and likely kill thousands of them each year. Creatures that tend to hang out near the ocean’s surface are especially vulnerable, such as whale sharks and sea turtles.

A good step toward decreasing collisions is figuring out where animals are most at risk, and that’s where this new whale shark study comes in. Large ships are required to report their locations, and the authors compared those points to the movement of hundreds of whale sharks, which they had previously tagged with satellite trackers. (This is no easy feat: “You’ve gotta have some nice long fins, a good pair of lungs, and sprint after it underwater,” said David Sims, a marine ecologist at the University of Southampton and a study co-author.)

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23453516/Screen_Shot_2022_05_11_at_1.03.39_PM.png) Womersley et al./Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Womersley et al./Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23453529/Screen_Shot_2022_05_11_at_1.09.08_PM.png) Womersley et al./Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Womersley et al./Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

The results revealed just how vulnerable these fish are: More than 90 percent of the ocean’s surface area that whale sharks use overlaps with the routes of tankers, passenger ships, and fishing vessels. Whale sharks tend to congregate near the coast, where shipping is especially busy, according to Freya Womersley, a doctoral student at the University of Southhampton and the study’s lead author.

She also discovered that many of the sharks’ tracking devices stopped working when the animals entered busy shipping lanes, perhaps because they were killed by ships. (Some trackers even showed sharks swimming into dense shipping routes and then sinking slowly to the seafloor — “the smoking gun for a lethal ship strike,” as Womersley and Sims wrote in The Conversation.)

Sharks cruising in the Gulf of Mexico, the Arabian Gulf, and the Red Sea were at the greatest risk of collision, according to Womersley. “Not only are they spending a lot of time at the surface where they may be vulnerable to being struck, but they’re also occupying the same places that some of these ships are moving through,” she told Vox.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23453668/GettyImages_472571350.jpg) David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

While scientists don’t know exactly how many sharks boats have killed, they do have this information for other marine giants including the North Atlantic right whales. Ships killed at least a third of the right whales that died in the last few years, and they injured more. Today, only about 360 remain. (“Right whales are notoriously bad at not being run over by ships,” Harcourt said.)

Other kinds of whales, mackerel sharks, otters, manatees, and a whole host of other creatures are vulnerable, too, according to the review. But physical strikes are only part of the problem.

While most humans perceive the world through sight and dogs see the world through smell, many whales and dolphins rely on sound. For them, sound is everything: It’s how they map their environment, find prey, and talk to each other, often through hundreds or thousands of miles of ocean.

Shipping throws a big, clanging wrench in this strategy. Over the last 50 years, there has been a 32-fold increase in low frequencies of sound along the world’s major shipping routes, largely caused by giant propellers. Some whales use those same frequencies to communicate. (Fish — including whale sharks — don’t use sonar to communicate, so this is likely not a big problem for them.)

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23453646/GettyImages_1240558573.jpg) CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

CFOTO/Future Publishing via Getty Images

As a result, in noisier areas, some whales seem to be getting louder, for the same reason you might yell when you’re talking to friends at a loud bar, said Daniel Costa, a marine ecologist at the University of California Santa Cruz who was not involved in the whale shark study. “Whales have already started speaking louder to make up for the increased noise,” he said.

Scientists have also discovered that sound can interfere with communication and disrupt behaviors such as hunting prey, sleeping, and mating. More than 150 studies have found that noise has significant effects on marine life, according to a recent review. (I recommend listening to some of this six-minute audio track that accompanies the paper. You can hear what the ocean sounds like with and without shipping.)

Big cargo ships also pollute the air with carbon emissions. They use some of the dirtiest fuel on the planet and produce a similar amount of carbon emissions as the aviation industry (roughly 3 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions), as Vox’s Umair Irfan reports.

Those emissions accelerate climate change, which harms all kinds of marine life. Ironically, warming can even make some animals more prone to ship strikes. For example, North Atlantic right whales are traveling north into Canadian waters in the spring and summer as the ocean warms, where until recently they weren’t protected against ship strikes. “Climate change keeps reshuffling the deck,” making it hard for regulations to keep up, Costa said.

Making oceans safer for marine giants is conceptually simple, and one option is to route ships away from animal hot spots. A 2015 study, for example, found that shifting a shipping lane near Sri Lanka just 15 nautical miles south could reduce the risk of ships hitting blue whales by 95 percent. (Advocates are now pushing for this change.)

Even just slowing ships down can make a huge difference. The chance that a cargo ship will kill a whale falls to below 50 percent when it’s moving at around half speed (10 knots, or 11.5 miles per hour), compared to nearly 100 percent when it’s moving more quickly, according to one 2006 study.

This so- called “slow steaming” is also less noisy and requires less fuel. Just a 10 percent speed reduction may lead to a 19 percent cut in greenhouse gas emissions, as Irfan reports. And the fuel bill is cheaper, too.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23453490/mms_098_f3.gif) Angelia Vanderlaan & Christopher Taggart/Marine Mammal Science

Angelia Vanderlaan & Christopher Taggart/Marine Mammal Science

But there’s a big drawback to ships slowing down or going on a different route: It takes longer to deliver goods. That’s one reason studies like this don’t always translate into shipping restrictions. That drawback also makes alternative approaches, such as designing quieter ships or adding wildlife deterrents or propeller guards, appealing (although the benefits of these technologies aren’t well established).

But other than shopping locally to reduce shipping, it’s something we can do right now, Womersley said, and the payoff would be massive. Many marine giants are at the top of the food chain, where they stabilize ocean ecosystems. They also help fertilize the ocean and capture huge amounts of carbon that could otherwise fuel climate change, as old- growth trees do. These animals are also awesome. They don’t just include the largest fish on Earth, but the largest animal to have ever lived (the blue whale). All of which makes getting our goods a little bit later seem like a pretty reasonable trade-off.

My dog loves to eat garbage. Why do I spend so much on pet food?

My dog, Jumanji, loves beef pizzle — also known as bully sticks. Also known as dried bull penises.

I can tolerate what they are, and even the pungent smell these things exude. What’s harder to stomach is the price tag. Each stick can cost more than $10, and my dog tears through them in a matter of minutes.

Bully sticks aren’t the only pricey pet products. Foods, treats, and chews can cost owners hundreds of dollars a month, even though they’re often made with “byproducts” of the meat and poultry industry — essentially, anything that’s not muscle tissue, like udders, spleens, bones, and, yes, pizzle.

These costs are hitting more people than ever before. During the pandemic, a whopping 23 million American households — about one in five — adopted a dog or cat. And the prices are rising, too. Pet food was roughly 12 percent more expensive at the start of this year compared to early 2020, according to the research firm NielsenIQ.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23450836/IMG_8282_2.jpg) Benji Jones

Benji Jones

Cat or dog, mutt or purebred, your pet is probably pretty expensive, and there’s a reason why food and treats are such a big part of the cost. For one, “byproducts” aren’t really byproducts as you might think of them. More importantly, though, dog and cat owners have a trait that makes us especially vulnerable consumers: We are completely obsessed with our pets.

In a strange way, kibble is like infant formula, according to Marion Nestle, a professor emerita of nutrition at New York University who’s written two books on pet food: “You have a product that is the entire nutrition for that animal.”

Those homely brown pellets need to have the right combination of fat, protein, fiber, and nutrients to keep a pet healthy, even if it eats nothing else. (The adult equivalent might be something like Soylent.)

Kibble also needs to last for weeks or months without rotting, which requires additional ingredients. “The complexity is just amazing,” George Collings, a pet food consultant, told me, adding that juggling multiple supply chains and thousands of ingredients comes at a cost.

The ingredients can be pricey themselves, too — even the so-called byproducts of the meat industry. While Americans might not readily eat meats like liver and pizzle, there’s a market for them elsewhere, such as in Europe and China. That’s why some experts call “byproducts” a misnomer.

“They’re not scraps,” said Jennifer Martin, an assistant professor of animal science at Colorado State University. “They’re high-demand proteins and high- demand ingredients that the pet food industry has to compete for.”

The pandemic has also boosted meat prices overall. A couple of years ago, outbreaks of Covid-19 forced meatpacking plants to close. Farms responded by euthanizing an enormous number of animals, which squeezed supply and boosted costs. Those costs trickled down to the pet food industry, said Dana Brooks, president and CEO of the Pet Food Institute, an industry trade group.

<img alt="A dog sniffs at a bowl of kibble labeled with a 3 while ignoring bowls 1 and 2." src=“https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/thumbor/vrJQsPnjJF-kD0icY6c-Er_tH3o=/800x0/filters:no_upscale()/cdn.vox- cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23450847/GettyImages_658383045.jpg” /> Getty Images

Pet food producers also pour money into research. The goal, Nestle said, is to make a kibble that’s just gamey enough — that “tastes bad enough” — so that animals love it but it doesn’t smell or look so awful that people won’t buy it.

Companies run sniff tests with pets to find the most palatable kibble, Martin said. They put out a few different formulations of a particular food in a large room and then unleash dozens of dogs (or a handful of cats) to see which foods they prefer. “They really enjoy getting to participate in this process,” Martin said.

Bully sticks, specifically, face additional challenges that impact their price — such as the one rooted in biology. Only bulls have pizzles, and they only have one. Plus, manufacturers can generally only get a couple of sticks per penis, Martin said. The faltering reputation of rawhide chews has also buoyed demand for bully sticks, she said.

Like any good company, pet food producers know their customers well; they know that humans love their animals and will do pretty much anything for them. So another reason why pet food companies charge so much is simply “because they can get away with it,” Nestle said.

Companies also know that people are paying more attention to what’s in pet food, perhaps, because they’re spending more time at home with their animals. Owners are increasingly opting for foods that are similar to what they might buy for themselves — all-natural, non-GMO, vegan, and so on. Usually, pet food trends lag about five years behind our own, yet that gap is shrinking, Martin said. “The pets don’t care about anything that’s on the label, but the owners do,” Nestle said. “They’re not selling to the pets.”

This gets at a much bigger idea: The pet food industry is, to a large extent, built on branding. If you put peanut butter in a tube and call it “Kong Stuff’n,” you can sell it for more than a jar of Jif. “They know we’ll pay for it,” Martin said. The same list of ingredients packaged by different brands of food can also cost wildly different amounts, Nestle said.

Marketing also obscures the fact that there are just a handful of major corporations behind the majority of food brands you see at the pet store. For example, Mars Petcare — a subsidiary of Mars, best known for making M&Ms and Twix bars — owns dozens of brands including Pedigree, Greenies, Iams, Whiskas, and Royal Canin. Nestle Purina, a subsidiary of Nestle, also has several brands to its name including Purina, Friskies, Beneful, Fancy Feast, and many others. A lack of competition within an industry can be bad for the consumer and bad for prices.

Brooks, of the Pet Food Institute, argues that the pet food industry is still highly competitive. And to that end, a raft of startups, from firms offering vegan meals to online retailers, now threatens to shake up the industry, which some analysts say could triple in size over the next decade.

Remarkably, there’s not much research that compares the cost of dog or cat food to the health outcomes of the animal, according to Joseph Bartges, a board- certified veterinary nutritionist at the University of Georgia. “Expensive does not necessarily mean better,” Bartges said in an email. “There are no good studies evaluating this.”

That leaves a big opportunity for the industry, Shari White, Petco’s senior vice president of merchandising, told me. “I’d love to see more research on health outcomes,” she said. (She noted that Petco consults with a team of trained nutritionists and vets, and partners with brands that carry out health-related research.)

Popular diets for dogs like “grain-free,” which tend to be pricier, may not be better either, Gimlet’s Rose Rimler reported last year for an episode of the podcast Science Vs. While some dogs do have grain allergies — and it’s important to be mindful of them — these canines have evolved with us, and they’ve evolved to eat grains, she reports. (The whole episode is excellent and worth checking out.)

There’s also not much evidence that feeding table scraps to your pup on occasion is a bad idea, Bartges said, as long as you avoid foods they can’t tolerate, like macadamia nuts and chocolate. (You can find a full list here.)

Absent more information, it’s hard to know what to buy — and, as pet food author Nestle said, it’s easy to see why pet food companies might want to keep it that way. “The appeal of the more expensive foods is to pet owners who want to do right by their pets because they love them,” Nestle said. “The pet couldn’t possibly care.”

Was it a minor contributor or a major factor in the US’s inflation woes?

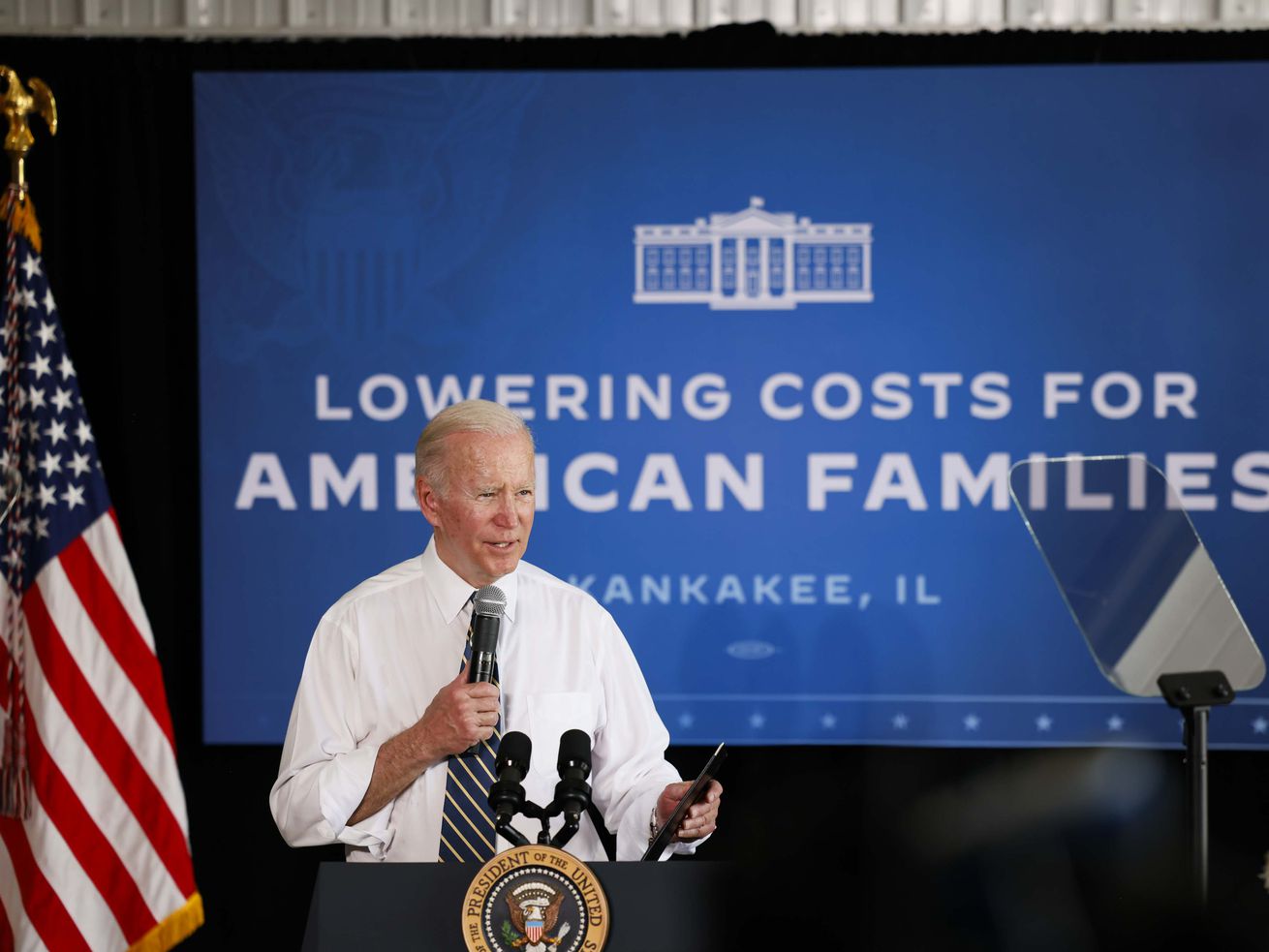

With President Joe Biden’s legislative agenda stalled in Congress, the American Rescue Plan — the $1.9 trillion stimulus bill Democrats passed in March 2021 — may stand as his biggest achievement.

But did it contribute to the country’s current inflationary mess?

The massive spending law, which included $1,400 checks for each person in a family, generous expansions to unemployment insurance and child tax credit benefits, and hundreds of billions in aid to state and local governments, was intended to help people in need and stimulate economic demand, and it did.

Some economists argue, though, that all this came at the cost of making inflation worse. New Consumer Price Index numbers released Wednesday showed prices up 8.3 percent compared to one year before. And “core inflation,” which excludes volatile energy and food prices, rose 0.6 percent in just one month.

Countries around the world are struggling with inflation due to pandemic disruptions, but the Biden stimulus made the US’s inflation problem more severe, to at least some extent. “I think we can say with certainty that we would have less inflation and fewer problems that we need to solve right now if the American Rescue Plan had been optimally sized,” said Wendy Edelberg, a senior fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution.

Inflation has brought with it two big problems. The first is already evident: Because most Americans’ wages haven’t risen enough to keep up with it, real (inflation-adjusted) wages have been declining at the highest rate in four decades.

The second problem is, if inflation remains so persistent, what reining it in could entail. The Federal Reserve has started raising interest rates in an effort to cool down the economy. They’re trying to do so gingerly, aiming for a “soft landing.” But if demand and investment end up plummeting in response, the US could face a painful recession.

What the future holds is uncertain, but to understand how we got here, it’s worth reassessing the past. The American Rescue Plan was drafted with good intentions, but it caused real problems.

It’s important to understand the broader context. Inflation has been happening across the world, caused by pandemic-related disruptions, and exacerbated this year by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s Covid-19 lockdowns. Even before the American Rescue Plan passed, “the seeds for a high-inflation environment were already planted,” said Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

But regarding the exact amount of inflation, the US stands out. And it started to stand out shortly after President Biden took office.

From 2021 onward, what’s known as “core inflation” has been significantly higher in the US than in other wealthy countries. (Core inflation is a common metric that excludes food and energy prices, which tend to be volatile, to try to get a better sense of general price levels and inflation in an economy.)

A recent article published by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco makes this point. The authors — Òscar Jordà, Celeste Liu, Fernanda Nechio, and Fabián Rivera-Reyes — compare core inflation in the US to the average of eight wealthy countries (the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Canada, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Finland). Before 2021, these and the US had similar inflation levels. Then the US’s shot up.

/cdn.vox-

cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23449332/Screen_Shot_2022_05_09_at_5.35.48_PM.png) Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

The authors don’t mince words about why they think that is, writing: “Estimates suggest that fiscal support measures designed to counteract the severity of the pandemic’s economic effect may have contributed to this divergence by raising inflation about 3 percentage points by the end of 2021.”

That is: The US did a lot more stimulus than these other countries, and now it’s seeing a lot more core inflation. And the stimulus that most stands out is Biden’s $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan — because it was enacted after more than $3 trillion had already been spent to stimulate the economy under Trump, with one big chunk of that being approved just three months prior.

“We put gasoline on the fire. That’s basically what the ARP did. It was almost written as if we didn’t just pass a trillion-dollar stimulus in December,” said Goldwein.

This core inflation divergence between the US and comparable countries continued into 2022, as Jason Furman, an economics professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, pointed out on Twitter (though it’s also worth noting Europe has been hit by rising energy and food costs after the Ukraine invasion).

U.S. inflation remains much higher than euro area inflation. This is the 12-month change in core HICP, a somewhat comparable measure for the two economies.

— Jason Furman (@jasonfurman) April 12, 2022

The US has consistently been ~4pp higher than Europe. That is a HUGE difference. pic.twitter.com/pboWfRluRR

There’s a range of opinion among economists on how much of the US’s higher inflation over 2021 (a 7 percentage point increase including energy and food prices, and a 5.5 percentage point increase excluding them) can be attributed to the American Rescue Plan. Michael Strain of the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute has estimated the law added 3 percentage points. Dean Baker of the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research, though, put that number at 1-2 percentage points.

Some economists with lower-end estimates still argue that it’s a mistake to put too much blame on the American Rescue Plan, which in their view was just a minor contributor to inflation. The White House shares this view. A senior White House official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said there were other potential explanations for differing core inflation rates in the US and Europe, and that arguments blaming Biden’s stimulus were merely correlational.

The US also stands out from other countries in a more favorable way: It had a quicker and stronger economic recovery in 2021. That indeed seems to be partly because of the Biden stimulus spending.

International comparisons, though, suggest the US would have bounced back without the American Rescue Plan, though more slowly. “I think we would have had a slower recovery, we would’ve had more suffering along the way,” Furman said in an interview. “But pretty much everyone, including countries that did basically nothing, has recovered. And the side effects [in the US] have been quite problematic.”

And if temporary help has worsened to a longer-term inflation problem, that isn’t great. Wages, when adjusted for inflation, have seen their most dramatic yearly drop in 40 years. A major fear is that inflation will become (or is already becoming) a self-fulfilling prophecy, as consumers and producers come to expect it and act accordingly. Then a different sort of economic pain could lie ahead as the Fed tries to get inflation under control. “Ultimately, if you have a situation where wages aren’t keeping up with prices and the risk of recession is really quite high, that’s not a good situation to be in,” Strain said.

The case that the American Rescue Plan contributed to inflation has three parts: its size, its timing, and the details of its spending.

First, the size: $1.9 trillion. Many economic analysts at the time argued that this was too big. saying their models showed so much new spending (on top of trillions already spent) wasn’t necessary to stimulate the economy, and risked overheating it and causing inflation. “I was on the expansionary side of every fiscal debate of my life up until last year,” said Furman. “But quantities matter. It can’t just be that more is better.”

In early 2021, a group of 10 Republican senators had proposed a $618 billion stimulus as a counteroffer to Biden’s. But Democrats, haunted by what they believed to have been policy mistakes from the Obama administration, rejected this, and decided going as big as they could was preferable to possibly spending too little.

“The sweet spot, I think, might have been a $300-500 billion American Rescue Plan,” said Strain. “That could have given us a lot of the benefits of the ARP without sparking such rapid price growth. The ARP was so big that the kind of marginal dollar went to inflation, not to increased economic output.”

Second was timing: that money was mostly spent quickly (about half was spent last year), rather than spread out over a longer period of time. This sent a lot of money flowing into the economy last year — which was the goal — except supply couldn’t keep up, and prices rose.

Third was composition: what the plan included. Much of the ARP’s spending did quite a lot to help people in need, with child poverty and child hunger falling. But other parts were not well-targeted. $350 billion was allotted to state and local governments under the outdated assumption that they’d be facing budget crises, but by early 2021 it was already clear most states weren’t facing such crises. (The White House official argued that while many states might not have needed the money, cities still did, and that these funds have been spent more slowly, so they probably haven’t contributed to inflation much yet.)

The checks were another issue. Birthed out of a political promise Democrats made to one-up Trump and try to win the Georgia Senate runoffs, the checks totaled about $400 billion in spending, and some of them went to families whose finances were already in fine shape. Giving money to people who don’t need it isn’t necessarily a bad thing in and of itself. But if the consequences are higher inflation and economic woes affecting everyone, well, it is a big deal.

“Had we made the checks smaller and more targeted, and spread out over time. I think we would’ve had less unwelcome inflation and a slower recovery in real activity,” said Edelberg. “That’s probably a trade-off, in retrospect, that would’ve been a good one to take.”

Meanwhile, the plan’s anti-poverty benefits proved to be temporary, when the expanded child tax credit expired at the end of 2021. Democrats had hoped to extend it further in the Build Back Better legislation, but Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) effectively killed that bill last December, citing inflation concerns. Manchin was always skeptical about the expanded child tax credit on the merits, but rising inflation surely didn’t help Democrats’ case for further big spending.

High inflation is now here, and the worse and more persistent inflation is, the more likely it is that the Fed will raise rates to get it under control, and cause a recession.

It’s true that the American Rescue Plan wasn’t the primary cause of today’s inflation. But if inflation was always going to be a problem, then it’s important to avoid policies that could make it a much worse problem.

In retrospect, it seems that Democrats simply didn’t take this seriously enough back in early 2021. They wrongly concluded that a stimulus far in excess of what models said was necessary was the less risky option. They thought they were still in the “money printer go brrr” era, where there was less pressure to be judicious about where that money was going — so instead of targeting help to those who needed it, they sent hundreds of billions of dollars to well-off Americans and states doing just fine, for political reasons.

Now, Democrats had many good intentions in drafting the American Rescue Plan — they wanted to help people and avert economic pain. And they had some successes, like low unemployment and strong GDP growth. But wages haven’t kept up with prices. And if this results in significantly worse economic problems in 2022, 2023, and 2024, not to mention electoral consequences for Democrats, it’s unclear whether it would have been worth it.

“We need to see whether we can really achieve a soft landing without bringing about a recession that involves a lot of pain,” Edelberg said. “Whether this all has a happy ending is still yet to be determined.”

Scruples, Imperial Power, Forever Together, Yukan and De Villiers excel -

Shah Rukh Khan’s Knight Riders Group acquires new Abu Dhabi franchise - The UAE will be the fourth country in which the Knight Riders Group will be associated with a T20 franchise

Uber Cup: Sindhu-led India loses to Thailand in quarterfinals - Thailand took an unassailable 3-0 lead, the remaining two matches of the tie became redundant and were not played.

24th Summer Deaflympics | Shuttler Jerlin Anika wins three gold medals - The badminton player has won several medals for the country at national and international level events

He has typhoid or something like that is what the doctor told me: Pant on Shaw - Shaw was on Sunday admitted to a hospital due to a high fever. He had himself shared an Instagram post from his hospital bed, saying he is hopeful of coming back soon

Experts share facts on saving grains from pests - Fumigation and alternative methods for safe storage and trade of foodgrains discussed at webinar hosted by CSIR-CFTRI

Karnataka govt takes ordinance route to implement “anti-conversion law” - The bill that was passed by the Legislative Assembly provides for protection of right to freedom of religion and prohibition of unlawful conversion from one religion to another by misrepresentation, force, undue influence, coercion, allurement or by any fraudulent means.

Andhra Pradesh: Election to four RS seats on June 10 -

Award for expatriate -

Passport Office to remain closed on May 16 -

Finland Nato: Russia threatens to retaliate over membership move - Finland’s leaders say they want the country to apply for membership of the alliance “without delay”.

Hard to see a way back for Putin, says UK PM - Boris Johnson says he cannot see how relations with the Russian leader can be ‘renormalised’.

Ukraine war: Russia pushed back from Kharkiv - report from front line - Correspondent Quentin Sommerville and cameraman Darren Conway are with Ukrainian troops as they advance.

Ukraine war: Snake Island and battle for control in Black Sea - This rocky outcrop has been fiercely contested for weeks and has vital strategic importance.

Covid mask rules relaxed for EU air travel - Masks will no longer have to be worn on EU flights and in airports from next Monday, new guidance says.

Baby formula shortage worsens as national out-of-stock rate hits 43% - Supply chain issues, recalls, and inflation have all contributed to the shortage. - link

Backdoor in public repository used new form of attack to target big firms - Dependency confusion attacks exploit our trust in public code repositories. - link

Intel squeezes desktop Alder Lake CPUs into laptops with Core HX-series chips - New chips will be faster and hotter than the current H-series processors. - link

AMD Ryzen 6000 gets DisplayPort 2.0-certified, testing on other products ramps up - VESA demos uncompressed 4K at 144 Hz with certified reference silicon. - link

Google teases future hardware: The Pixel 7, Pixel Tablet, and AR Goggles - Google heads off leakers with a pair of product confirmations and one prototype. - link

I was born female and transitioned to male. Early on in my transition, my gf and I were playing a video game, and I called her a noob when she died.

Her: Yeah okay Pinocchio.

Me: Pinocchio.

Her: You know… “I want to be a real boy!”

submitted by /u/Dasari11

[link] [comments]

Baffled and full of questions he is being shown around by God.

“Why am I here? I am an atheist.”

“That does not matter, all good people end up here.”

As they pass by a gay couple kissing the atheist wonders

“Isn’t that a sin?” Can I get Covid here?

“That does not matter, all good people end up here.”

They come by a Galactic Rebel, silently meditating.

"Wait, so you even take in people who believe in the Force?

“That does not matter, all good people end up here.”

Surprised, but intrigued the atheist looks around - when one last question comes to his mind

“But where are all the Christians?”

“Well… all good people end up here.”

submitted by /u/YZXFILE

[link] [comments]

its called plagiarism

submitted by /u/happycamper1377

[link] [comments]

I said “looking for cheap flights.”

She got very exited and said “I love you,” then got on her knees and

gave me the best blow job I’ve ever had.

Which surprised me as she’s never been interested in darts before.

submitted by /u/Buddy2269

[link] [comments]

Between 18 and 22, a woman is like Africa . Half discovered, half wild, fertile and naturally Beautiful!

Between 23 and 30, a woman is like Europe. Well developed and open to trade, especially for someone of real value.

Between 31 and 35, a woman is like Spain. Very hot, relaxed and convinced of her own beauty.

Between 36 and 40, a woman is like Greece. Gently aging but still a warm and desirable place to visit.

Between 41 and 50, a woman is like Great Britain. With a glorious and all conquering past.

Between 51 and 60, a woman is like Israel. Has been through war, doesn’t make the same mistakes twice, and takes care of business.

Between 61 and 70, a woman is like Canada. Self-preserving, but open to meeting new people.

After 70, she becomes Tibet. Wildly beautiful, with a mysterious past and the wisdom of the ages. An adventurous spirit and a thirst for spiritual knowledge.

THE GEOGRAPHY OF A MAN

Between 1 and 100, a man is like North Korea and Russia: Ruled by a pair of nuts.

submitted by /u/Yugan-Dali

[link] [comments]